17 July "Exhibition opens"

Harding visited an annual exhibition for the first time in July 1924. The Egypt Exploration Society's exhibition of objects from its season at Amarna was on at the Society of Antiquaries. Harding saw an ad in the newspaper about it and went along. There he was introduced to the archaeological network and followed his visit with another – this time to Flinders Petrie’s exhibition of antiquities from Qau, Egypt at University College London. Two years later, Petrie engaged Harding as an assistant on his excavations in Palestine.

Petrie had been holding exhibitions in London since 1884 to showcase excavations he (and eventually his students) conducted in Egypt. These temporary displays were arranged in the aftermath of excavation, once excavated objects had reached Britain.

Antiquities discovered during the excavation season (c. November to May) were placed on tables and shelves distributed into one or two rooms with plans, maps, paintings and photographs of the site and surrounding region on the walls. These events were open to the public with hours of admission that often extended into the evening after businesses had closed.

During this period, film screenings were a new addition to ‘exhibition season’. Hilary Waddington’s films of EES excavations at Amarna were the subject of the Filming Antiquity launch event – one of these films was screened in London in 1931 to complement the EES’s exhibition during its opening week. Although this screening was targeted at EES subscribers free tickets were also offered to the public.

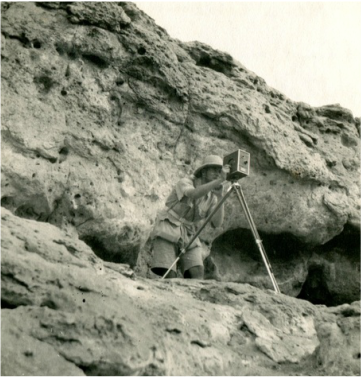

In 1935, notices appeared that a film of the Wellcome Expedition's excavations at Tell ed-Duweir (Lachish) would be screened twice a day at the exhibition, held at the Wellcome Museum on Euston Road. Film screenings of excavations in progress were also incorporated into the 1937 and 1938 Lachish exhibitions.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about the creation and initial screening of these Lachish films; in the course of the Filming Antiquity project we hope to find out more about them to contribute to our understanding of the films in Harding's archive.

The growing number of excavation films emerging from the shadows and the context of their initial display enables us to see histories of excavation and archaeology’s public impact in a whole new light. The legacy of the Lachish films continues into more contemporary times; clips from the footage were shown at the British Museum in 1990 in the Archaeology and the Bible exhibition.* I'd love to know what the 51,000 odd visitors to this exhibition thought of the vintage scenes!

References/Further Reading

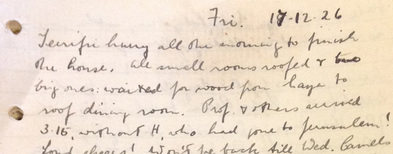

Harding, G. L. 1933. Diary Entry. [manuscript]. 17 July. Harding Archive: UCL Institute of Archaeology.

Director [Starkey, J. L.]. 1936. [Statement of recommendation]. Harding Archive: UCL Institute of Archaeology.

Naunton, C. 2010. The Film Record of the Egypt Exploration Society’s Excavations at Tell el-Amarna. KMT 21: 45-53.

Thornton, A 2015. Exhibition Season: Annual Archaeological Exhibitions in London, 1880s-1930s. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology 25(1):2, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bha.252

The Times. 1931. Egypt Exploration Society. Times Digital Archive, 7 Sep P 13.

Anon. 1938. J. L. Starkey. Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. British Newspaper Archive, 12 January.

*Thanks to Jonathan Tubb for this information.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed