This is my third article for the Filming Antiquity blog regarding Harding’s archaeology footage and links in with my first and second articles ‘Living at Lachish – Life in Camp’ and ’Olive Starkey – Lady of Lachish’, where there is other information and photos. There are a couple of references to James Leslie Starkey's wife Marjorie (known as Madge) in the Living at Lachish article too. All the Photos in this article are from the family collection unless otherwise stated.

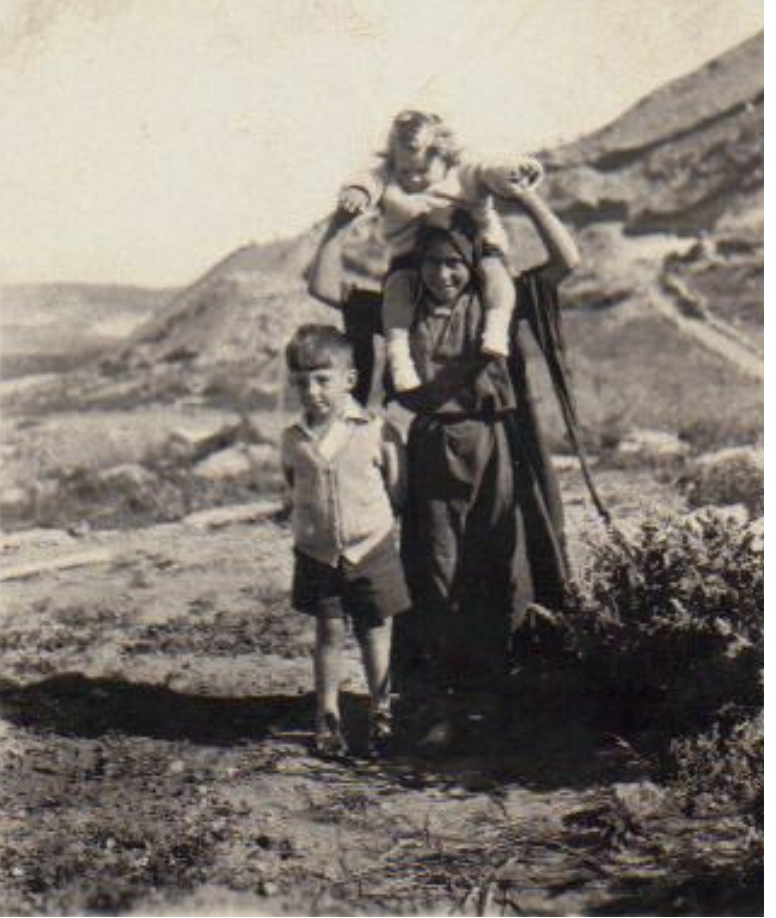

There is brief footage of Madge and the children on Harding films, and the official Lachish promotional film used in the 1930s, but as yet the extracts posted on the site only include shots of Leslie.

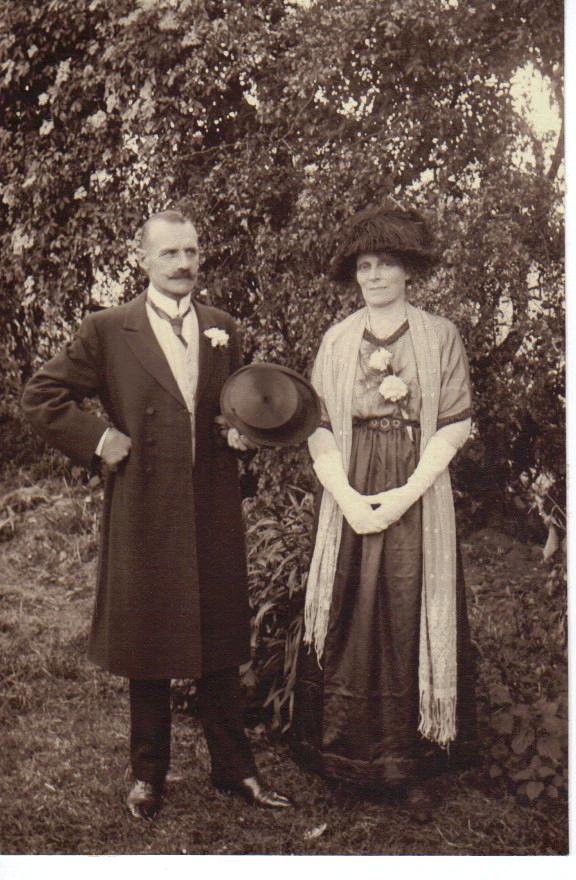

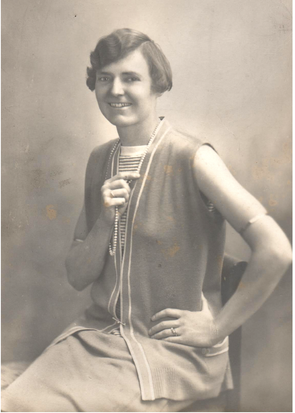

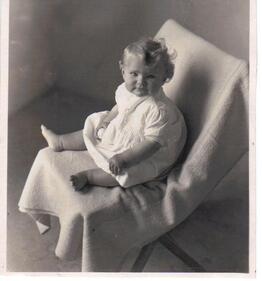

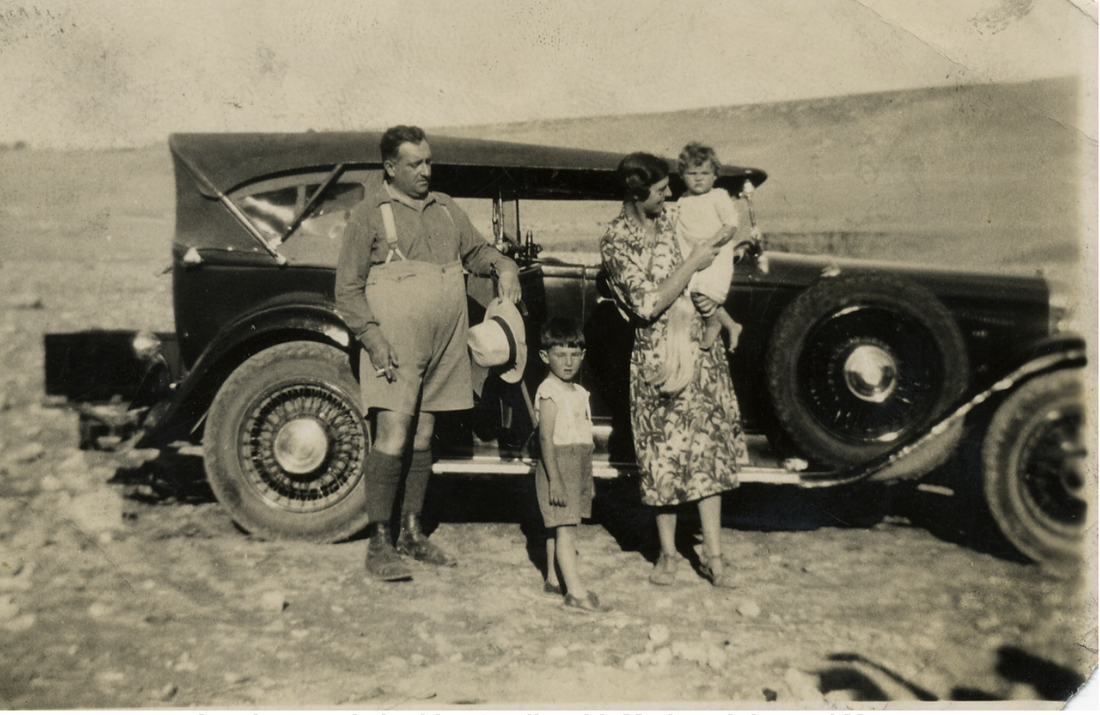

James Leslie Starkey was my Grandfather, my Mother Mary’s Father, but he died before I was born so I never knew him. In fact he died while his children, John, Mary and Jane, were still very young so to a great extent neither did they. However their Mother, Marjorie ‘Madge’ Starkey (my Grandmother) put together a scrapbook for each of them so that they should know something of him and about him and of his work when they were old enough to understand. So it is only owing to her careful preservation of the records, photographs, publications and many, many newspaper articles etc. that I am able to reproduce some of it in my articles. Unfortunately Grandmother also died before I was born so I never knew her either but I know lots about her from my mother Mary and my uncle John.

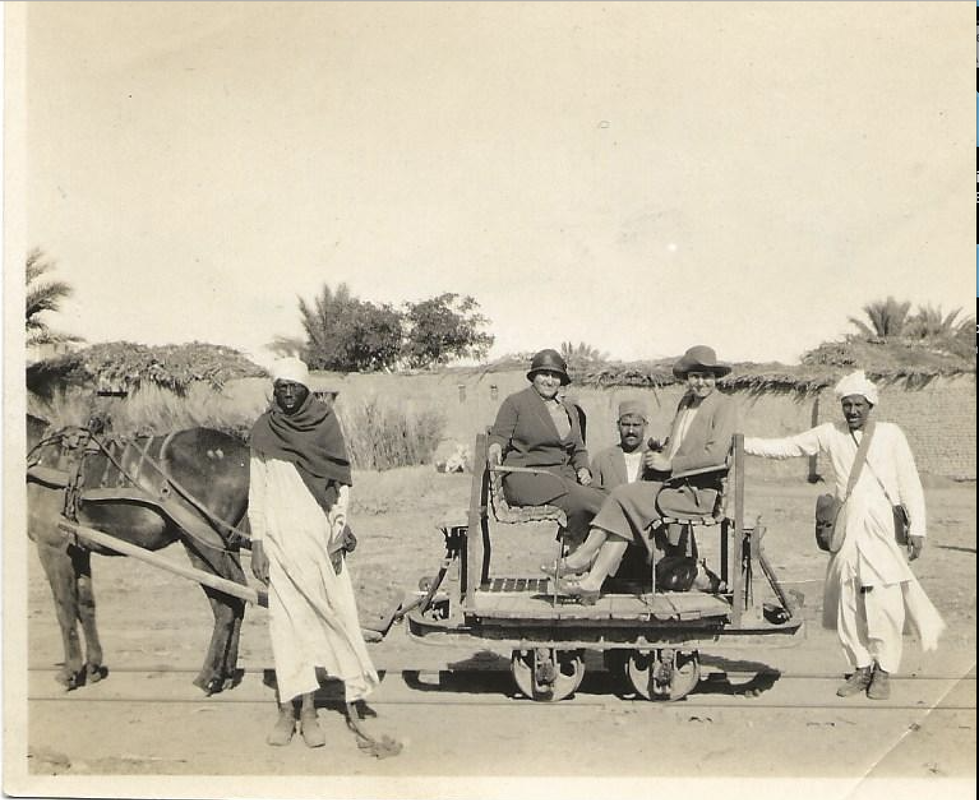

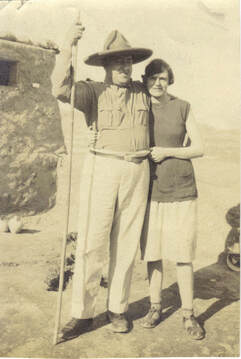

Outside the Dig House at Tell Jemmeh Petrie, Lady Petrie, Starkey with his cane, Madge, Dr. G. Parker, Mrs and Lt. D.L. Risdon Photo: W. Slaninka.

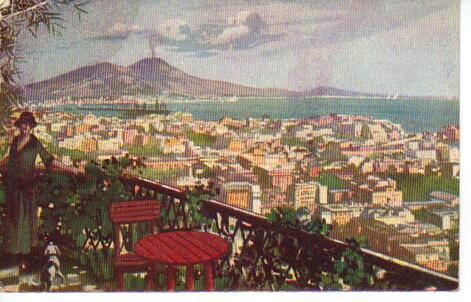

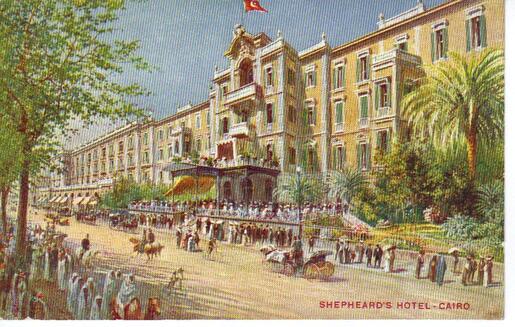

Outside the Dig House at Tell Jemmeh Petrie, Lady Petrie, Starkey with his cane, Madge, Dr. G. Parker, Mrs and Lt. D.L. Risdon Photo: W. Slaninka. Those from Madge include ‘My dearest Mother’ or ‘Dear Ma and Pa’ from the Shepherd’s Hotel, Cairo (a fashionable hotel founded in 1845) where they honeymooned! – her first trip abroad on the way to Karanis – ‘Here we are - We arrived last night – have been round the town – its so hot – am enjoying every moment’. Another was from Naples - ‘the weather is glorious – went to Pompeii yesterday – twas all wonderful and Naples! – well you should come and see it. Vesuvius smokes steadily away – at night one can see the red fire’. They were staying in Bertolini’s Palace Hotel which commanded a grand view of Vesuvius, Naples and the Bay – it is still there today.

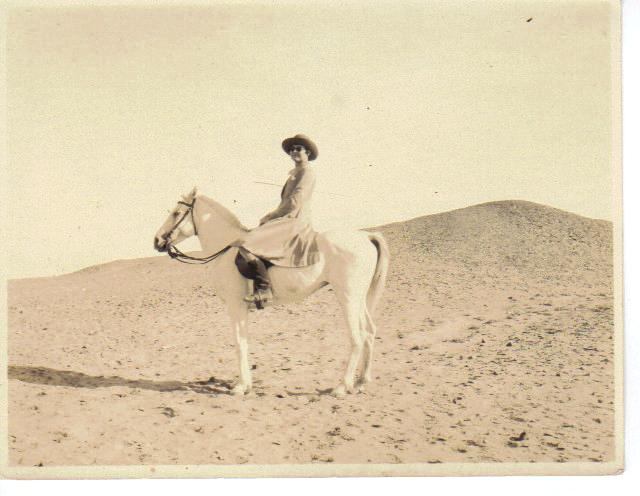

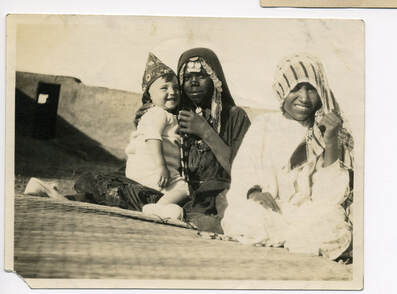

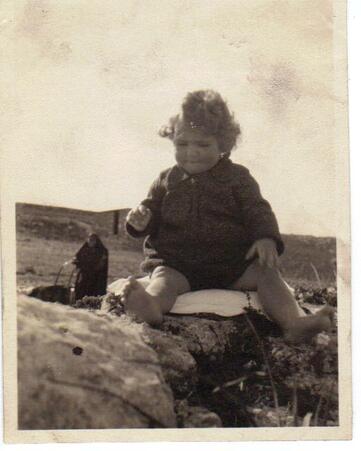

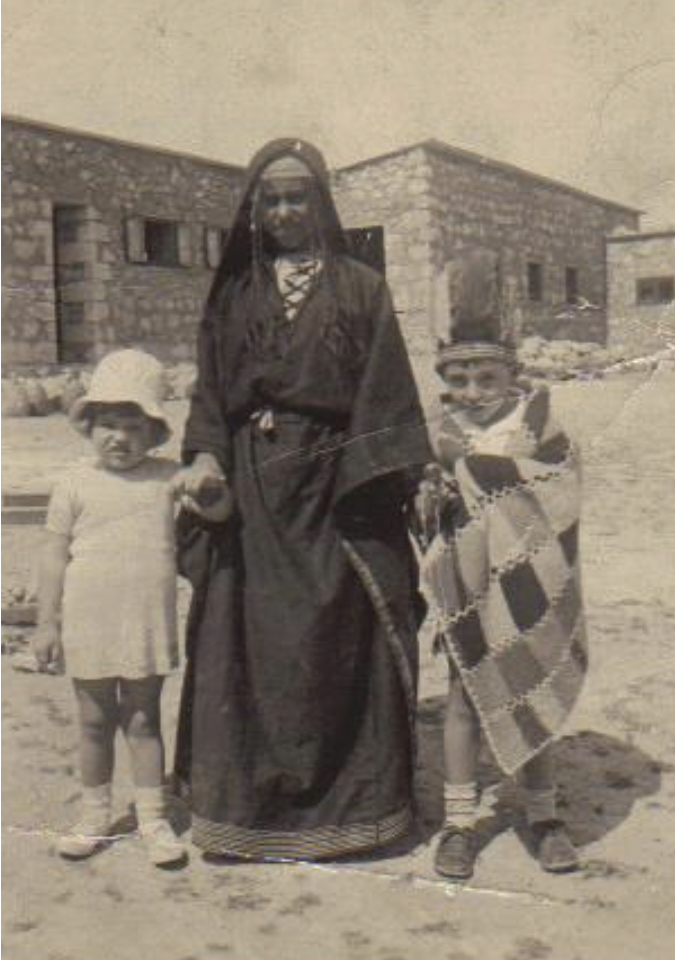

Whilst Madge’s role was as a Wife and Mother, and did not have any particular interest in the archaeology side of things, she did support Leslie in his work as the Director’s wife and would help out where she could; and also had the rather gruesome task of packing away skulls at Lachish for despatch to England, after they had been cleaned and waxed! Madge loved the Bedouins too, immersing herself in their culture and language, which she learnt, and their dress and music, even learning how to drum. One season Madge taught everyone how to knit, men and women alike, both the members of the team and the Bedouins, who begged to be taught – it was quite a craze and everyone was at it, knitting stockings and jumpers. Olga commented that it was so funny watching the houseboys with their big hands trying to weald the needles [see also ‘Camp Capers’ photo in ‘Life in Camp’ article with Madge in Fancy Dress]. All the time Madge was in Palestine she collected folk costumes, embroideries, jewellery, fabrics, textiles, etc. After her death Olga Tufnell arranged for Madge’s collection to be donated to the Palestine Heritage Museum in Jerusalem, where it is on display today.

She also helped Leslie in the preparations that had to be planned for camp visitors, and the stream of people who undertook field work and helped out in many ways over the years. As I mentioned earlier, her mother had made sure all her daughters were well groomed in homemaking skills and Madge was an excellent cook and hostess, as well as a wonderful, generous and loving wife to Leslie and mother to her children.

TO BE CONTINUED, with a further article on the tragedy and its aftermath.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed