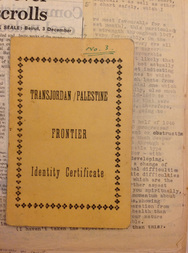

Harding’s films offer us a valuable glimpse into urban spaces in British Mandate Palestine and Transjordan. "Cityscapes" brings together Harding's footage of Amman, Jerash, Jerusalem and Gaza, documenting his encounters with each place in the early 1930s. The information below adds a further layer of detail, drawing on complementary material from the Harding and Horsfield archives at UCL Institute of Archaeology and my own photographs from a research trip to Jordan in 2008. In addition, I'm grateful to Yasmeen El Khoudary for contributing the section on Gaza in this post, and for providing details on the Gaza section in the film, and Felicity Cobbing for providing details on the Jerusalem sequence in the film.

In the Roman era, Amman was known as Philadelphia. Along with Jerash, it was part of a network of ten cities in the Levant - the “Decapolis”. The remains of Roman Philadelphia are still visible today, even though Amman has expanded significantly since Harding filmed it. The Roman theatre is in downtown Amman, and above it in the area known as the Citadel lie remains of the Roman acropolis with the ruins of a Roman temple.

When Harding filmed in Amman, it had been the capital of Transjordan for about a decade. It had a population of over 20,000 by the mid 1930s. Across the street from the Roman theatre was Amman’s Hotel Philadelphia, the only large hotel in the city for tourists. Nearby were the Government offices, among them the Transjordan Department of Antiquities. The residence of Emir Abdullah was also not far away.

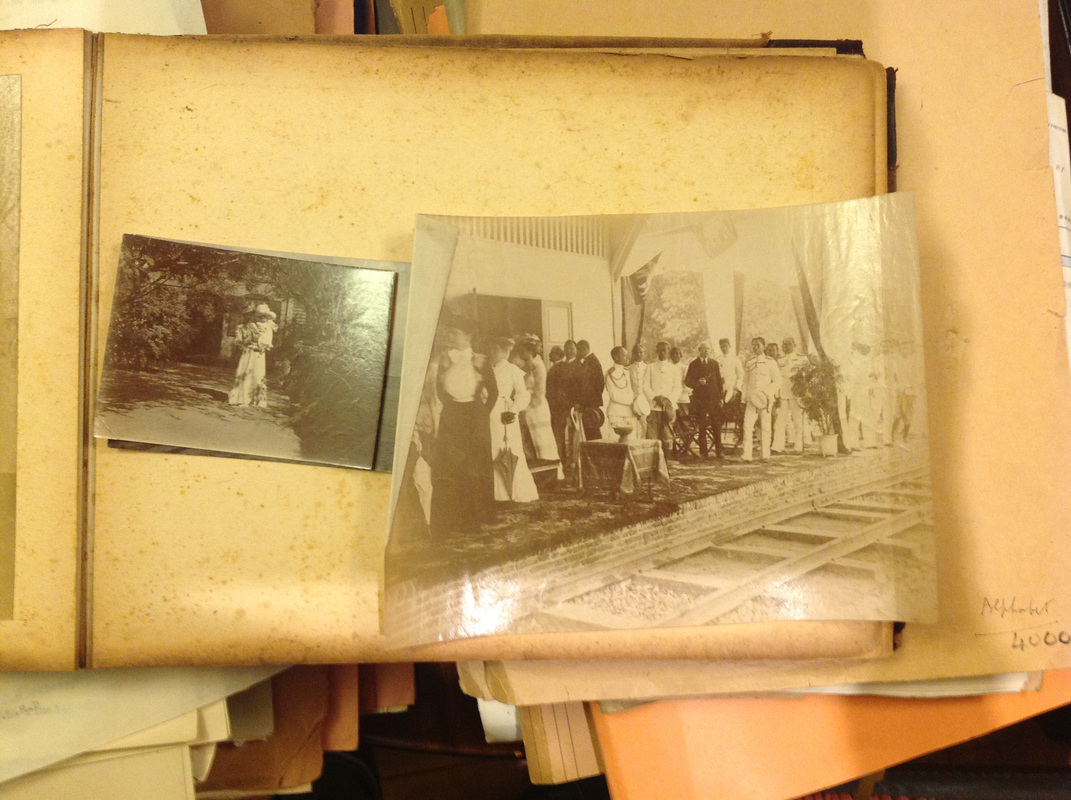

Jerash was a village north of Amman incorporating the ruins of the Decapolis city of Gerasa. When Harding arrived on site with his camera, the Transjordan Department of Antiquities had an outpost there, in an old Ottoman-era house right in the middle of the site, just above and to the right of the Propylea of Artemis. At the time, George Horsfield lived in the house; he was Chief Curator/Inspector of the Transjordan Department of Antiquities, responsible for overseeing work carried out in Jerash. Harding himself subsequently lived in Antiquity House, as it was called – he took up Horsfield’s post in 1936. After Harding’s death in 1979, his ashes were interred in Jerash.

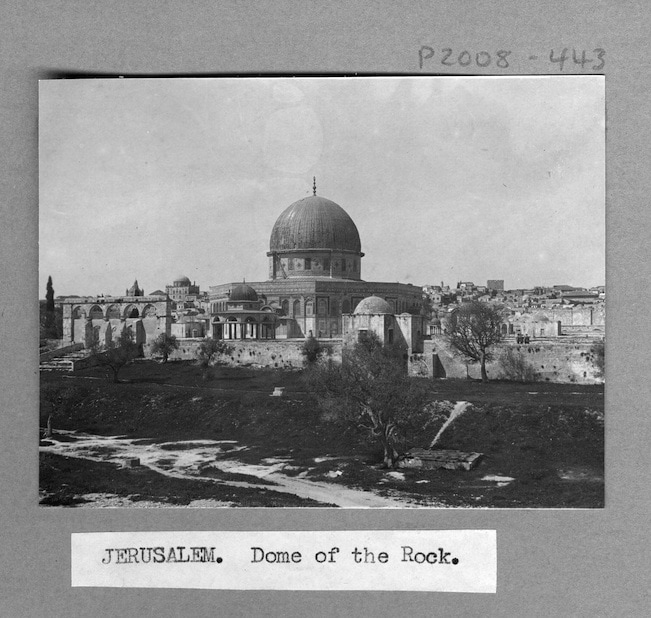

In filming Jerusalem, a city significant to millions across the world and a place of religious pilgrimage, Harding focuses on the southeastern part of the Old City, and one of the most well known buildings – the Dome of the Rock – and the other buildings on the Haram esh-Sharif/Temple Mount platform. Jerusalem was also significant for archaeologists as seat of the administrative framework for archaeology in Mandate Palestine. The Palestine Department of Antiquities and the Palestine Archaeological Museum (now Rockefeller Archaeological Museum) were both situated just outside the Old City walls near Herod’s Gate in East Jerusalem.

Harding and his colleagues in excavation often visited Gaza. If approaching Palestine from Egypt, a route taken by many tourists at the time, the railway began at Kantara East Station and stopped at Gaza en route to Jaffa and Tel-Aviv.

Two miles off Palestine's Mediterranean coast, Gaza has historically been one of the region’s most important trade cities.

The striking arch shown in the film lies to the south of the Mosque. It marks the entrance to Gaza’s famous gold market, also known as Souk al-Qissariya, which was built by the Mamluks during the 15th century. The covered market used to occupy a much larger area, most of which was destroyed by the British Army during WWI. Harding's camera also offers a different perspective of Share’ al-Bahar/Omar al-Mokhtar Street, looking east towards the city. This perspective shows the historic Khan al-Zeit (the Oil Quarter), which was recently replaced by a new high rise building.

Not far from the opposite end of Omar al-Mokhtar street lies one of the oldest pottery workshops in Gaza, Al-Fawakheer. Pottery and ceramics have been a staple of Gaza for thousands of years with local samples dating back to the Neolithic. During the Hellenistic era, the "Gaza Amphorae" became a renowned symbol of excellent olive oil, wine, or brie that was produced in the city and traded with cities around the Mediterranean coast.

El-Eini, R. 2008. Mandated Landscape: British Imperial Rule in Palestine 1929-1948. London: Routledge.

Feldman, I. 2008. Governing Gaza: Beaurocracy, Authority and the Work of Rule, 1917-1967. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Horsfield, G. 1933. A Guide to Jerash - With plan. Government of Transjordan.

Kraeling, C. (Ed). 1938. Gerasa, city of the Decapolis. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Luke, H. & Keith-Roach, E. 1930. Handbook to Palestine and Transjordan. London: Macmillan & Co.

Lumby, C. 1934. Traveller's Handbook to Palestine, Syria and Iraq. 6th edn. London: Simpkin Marshall, Ltd.

St. Laurent, B. with Taşkömür, H. 2013. The Imperial Museum of Antiquities in Jerusalem, 1890-1930: An Alternate Narrative. Jerusalem Quarterly 55: 6-45.

Thornton, A. 2009. George Horsfield, conservation and the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. Antiquity Project Gallery.

Thornton, A. 2014. The Nobody: Exploring Archaeological Identity with George Horsfield (1882-1956). Archaeology International.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed