On looking at the footage I too believe it may be her, although as Caitlin says, all we see is a pair of hands (wearing a pretty bracelet) but they do look like her arms! Olive never went to Lachich (Tell Duweir) - with my detective hat on I believe this sequence may have been filmed in London. One of the photos below shows Olive wearing an overall and working on an object in a box next to a window – very similar to the footage which also shows what look like overall sleeves rolled up.

I would love to believe it is her, and thought the following additional personal and family information about her and her work may also be of interest as an addition to Caitlin’s post and film clip.

Caitlin refers to women "helping out" in the background of archaeology and I am glad to write this tribute to Olive as she was certainly one of the unsung Ladies of Lachish.

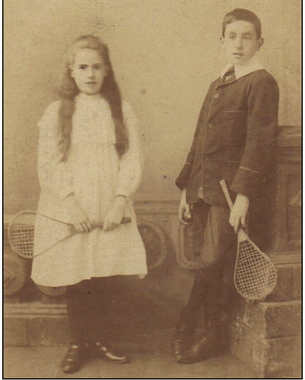

Her father was an Architect and Surveyor (James Starkey of St. Luke’s and Highbury), The Starkeys hailed from London and the family tree dates back to Roger Starkey, Mercer of London, who was granted a coat of arms in 1543 under the reign of King Henry VIII.

Olive and Leslie were children by their father’s second marriage in 1894 to the widow Louisa Brown (nee Pike) of Holloway. Their elder halfsisters, Louie and Eva Brown, were their Mother’s children from her first marriage Mr. Starkey had no children with his first wife Isabella who died in 1892.

She was intensely proud of her brother Leslie and wholeheartedly supported his work by painstakingly repairing, reconstructing and restoring the pots and decorated vessels which formed the collection from Lachish and had been sent back to the UK.

The pot being mended in Caitlin’s clip is definitely from Lachish; the finished article was a polychrome vase of about 1550 BC with figures of an ibex and fish one side and an ibex and bird the other side which was part of the expedition exhibitions of the 1930s and is now in the British Museum.

When the Emblem for Lachish was picked she made the Lachish Banner which was flown in the camp in Palestine. John had kept the Banner with him for over fifty years at his home in Canada and at the memorial service held in Jerusalem for his father in 1988 he presented it to Prof. David Ussishkin.

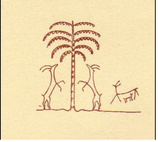

The design for the Lachish emblem was based on a painted potsherd - The Lachish Ewer – chosen by Sir Henry Wellcome himself. Olga Tuffnell told Mary (Leslie’s daughter) that she did many drafts before Sir Henry was satisfied with the result and It became the emblem of the expedition, appearing on all notepaper and allied paperwork, advertising and publications.

Olive was deeply affected by his death, but her love for her brother was such that she was determined to bring his work to fruition.

She tirelessly worked with Olga Tufnell after the war to bring the Lachish Books II, III and IV to completion - in between her A.R.P. work!* An article on Olive and Olga's work appeared in The Evening Standard in June 1940 entitled ‘‘Palestine Excavation Goes on – Two women direct it from London".

Olga always thanked Olive in the Lachish acknowledgements. For example, in Book II she wrote:

"Miss Olive Starkey has been at work on the repair and reconstruction of pottery since 1933 and has built up from sherds several hundred pots, including many fine decorated vessels which now make worthy additions to the museum collection. She has continued this task all year round and through her perseverance and skill has surmounted many technical difficulties."

In Book III Olga stated: "... and it is due to her great care and technical ability that the vessels are now fully restored". And in the final volume, Olga highlighted Olive's ‘deep and personal interest in the repair and reconstruction of several hundred pots’. Olive worked unstintingly with Olga until the final production of the last volume (in 1954). She had dedicated at least 21 years to this end.

I don’t know the origins of how she got into the business of sticking pots together (though we believe Leslie may have procured the job at the Institute for her when he became Director of Lachish) but I feel she must have been doing it before this even when Leslie worked for Petrie as her handwriting is on description cards in the Petrie collection too. She obviously had an eye for fine detail, and it also meant she was a godsend to the family when they had chinaware disasters! - her repairs were almost impossible to detect.

Olive’s eyesight had begun to deteriorate and she eventually retired to a Hotel in Folkestone for gentle folks – aptly named St. Olave’s!

She passed away December 1977, aged 81.

And ending on a more amusing note:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed