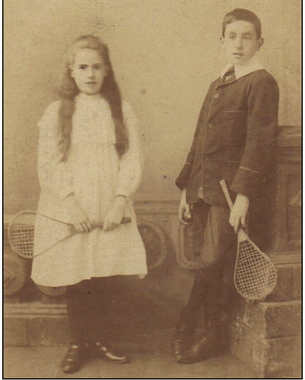

By Wendy Slaninka (Granddaughter of James Leslie Starkey & Marjorie Starkey by their daughter Mary)

This is my fifth article for the Filming Antiquity blog following on from ‘James Leslie Starkey, Archaeologist, Part 1, Background and Early Career’. It also links in with my first, second and third articles ‘Living at Lachish – Life in Camp’, ’Olive Starkey – Lady of Lachish’, (Leslie’s sister) and ‘First Lady of Lachish – Marjorie Starkey and her family’, where there is other information and photos of Leslie and Lachish.

Again, the inspiration for researching and finding out about my grandfather’s career was triggered by my Grandmother’s scrapbook mentioned in previous articles. It had languished in my mother’s sideboard for decades and it wasn’t until 2009 that I became particularly interested to investigate further. It has kept me captive ever since, gradually building on the original scrapbook – each tidbit and nugget of new information as exciting as I imagine excavating Lachish was for Grandfather – in a way I feel a sort of infinity with him as we are both in the business of digging into the past! I was also encouraged in this by Ros Henry who was Olga Tufnell’s assistant for a while in the 1950s.

I never knew my grandfather and his children were very young when he died so everything I write here about him and his work is gleaned from what others have said about him. His finds are well documented as is also the history of Lachish. As space here is limited I can only gloss over some of the facts I would like to include to give a flavour. Nevertheless it is such a large topic that to do him justice I will have to spread it over several parts. This first section will have to suffice only as an introduction to the site itself.

The man who knows and dwells in history adds a new dimension to his existence, he no longer lives in one place of present ways and thought, he lives in the whole space of life, past, present and dimly future

Sir Flinders Petrie (Methods and Aims in Archaeology)

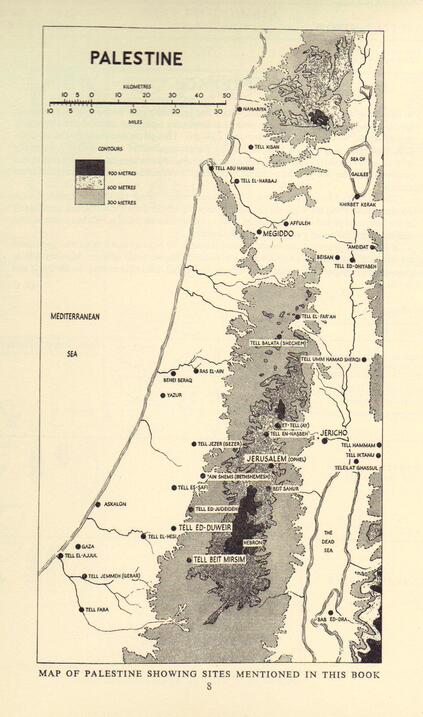

The site at Tell el Duweir had already been speculated upon by Prof. William Albright (The American School of Archaeology in Jerusalem) and Prof. John Garstang (Director British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem), and Starkey believed the site might disclose the Biblical Lachish for which archaeologists had long been searching. Petrie had already excavated Tel-es-Hesy and had claimed and published it as Lachish although it had not been proved and some experts were sceptical, including Starkey.

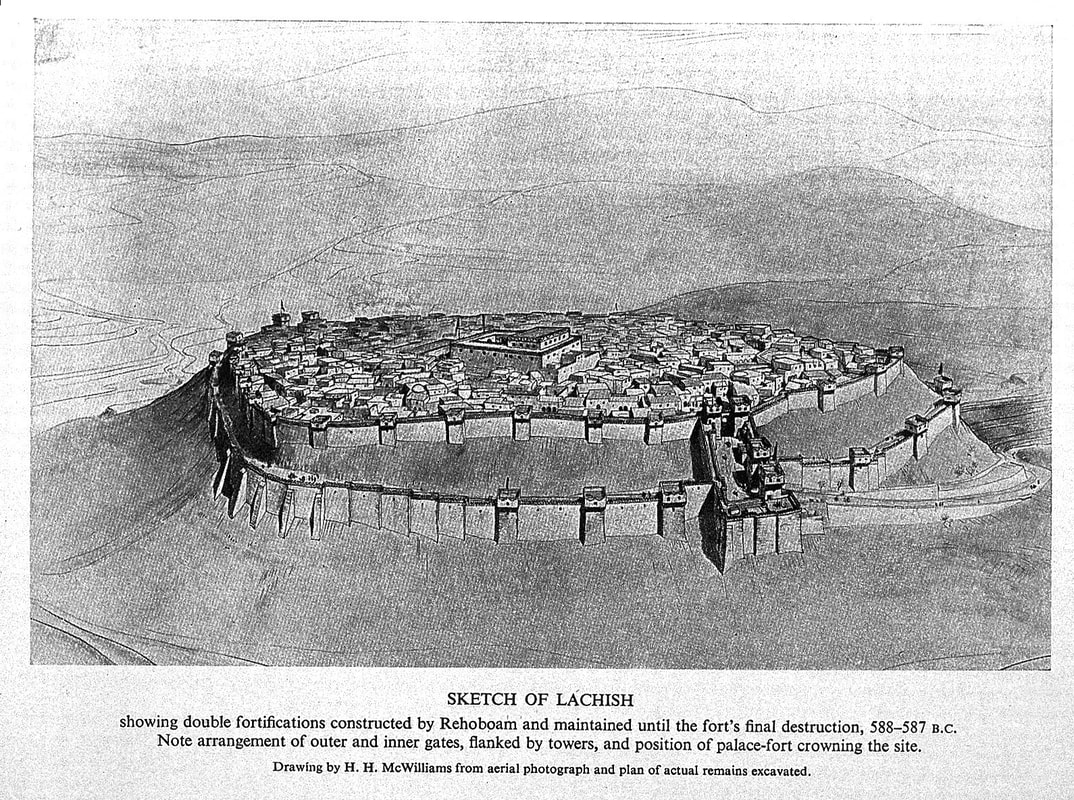

It is the most graphic war documentary ever found in the ancient world and Lachish’s excavated defences match in every detail the fortifications depicted by Sennarcharib’s war artist Sennarcharib was so pleased with his conquest the inscription below the reliefs read ’Sennarcharib, King of the World, King of Assyria, sat upon an ivory throne and passed in review the booty from Lachish’. The ‘Taylor Prism’ (a stone engraved column) also from the Palace gives Sennarcharib’s account of the conquest of Judah.

I was also particularly taken by the thousands of little oval shapes that entirely fill the space between the carved relief work. Apparently they represent the helmets of the thousands of soldiers.

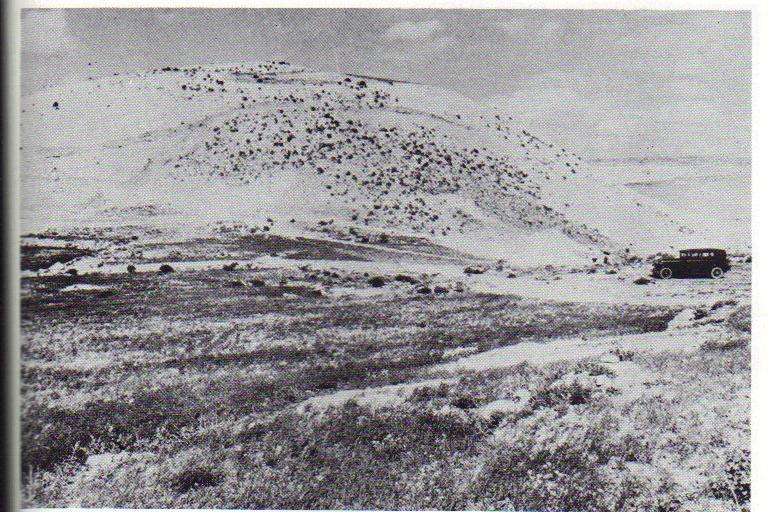

In fact at its height it was a more important city than Jerusalem, and double its size. It is estimated that there are at least ten or more different layers of occupation, with many cities built one on top of the other, including peoples from lower Egypt. The Hyksos from Egypt occupied the site in 18th century BC and there is also evidence that the city was destroyed by fire several times. During old testament times Lachish served an important protective function in defending Jerusalem and the interior of Judea and was one of the city forts guarding the canyons that led up to Jerusalem from the sea. It is the highest hill in that area and in order to take Jerusalem an invading army would first have to take Lachish which guarded the mountain pass.

One of the most characteristic features of the mound, was its steeply sloping sides, due to the defensive works of the Hyksos and the ‘glacis’, gleaming crushed white limestone sides, must have been an impressive and awesome sight to intending invaders. It is mentioned frequently in the Bible (Old Testament), including Joshua X: 5, 32-39, XII: 11, XV:39, Kings XIV: 19, XVIII: 14, 17, XIX 8, II Chronicles XI: 9, XXV: 27, XXXII: 9, Nehemiah XI: 30, Isaiah XXXVI: 2, XXXVII: 8, Jeremiah XXXIV: 7, Micah I: 13.

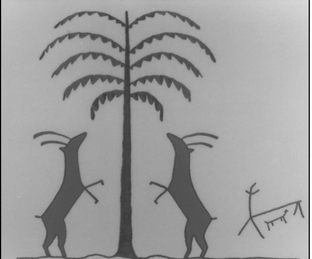

As many olive stones were found in the ashes and charred pieces of wood this event is presumed to have taken place around July or August (in fact this burning completely denuded this area of Palestine of its trees – Sennarcharib’s Reliefs had showed Lachish to be lush with grapes, olives and figs). As Judah trembled under the besieging of Lachish many villagers fled to Jerusalem, nearly trebling its population overnight.

Archaeological work in Jerusalem has proved this showing the population and size of Jerusalem at that time expanding from a city of about fifty acres to that of about 150 acres, spilling out beyond the confines of the old city walls. Thousands of captives from Lachish, Jerusalem and surroundings were taken back to Babylon, and these captives are mentioned in the Bible, weeping on the banks of the river in Babylon (‘By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion’, Psalm 137:1-3).[2]

With Starkey’s excavations however Lachish again burst into the light of fame with the impressive Fortifications and Gate visible from the top of the Tell. Starkey's achievements at Lachish, working the site year after year, added to the rich store of knowledge which the hill gave up under his skilled and patient direction.

To be continued in Part 2 (ii)

[Further References will be given at the end of the next Article]

Wellcome-Marston Archaeological Research Expedition to the Near East:

Lachish I, The Lachish Letters, OUP, 1938, Harry Torczyner, Lankaster Harding, Alkin Lewis, J. Starkey

Lachish II, The Fosse Temple, OUP, 1940, Olga Tufnell, Charles Inge, Lankaster Harding

Lachish III, The Iron Age (Text and Plates), OUP, 1953, Olga Tufnell et al

Lachish IV, The Bronze Age (Text and Plates), OUP, 1958, Olga Tufnell et al

Harding, G. Lankaster, 1943. Guide to Lachish Tell Ed Duweir. Government of Palestine, Department of Antiquities.

MacGregor, Neil, 2010. A History of the World in 100 objects – The Lachish Reliefs. BBC Radio 4.

Palestine Exploration Quarterly, June 1950. Excavations at Tell ed Duweir, Palestine, directed by the late J.L. Starkey 1932-1938, an address delivered by Olga Tufnell, pp 65-80.

Starkey, J.L. 1935. Finds from Biblical Lachish: A city of changing fortunes on the western frontier of Judah. Illustrated London News, 6 July [pp 19-21].

Ussishkin, David, 1979. On Tel Lachish, the biblical connections, and its first excavator, J.L. Starkey, Archaeological Newsletter of the Royal Ontario Museum, New Series, No.165.

Ussishkin, David. 2004. The Renewed Archaeological Excavations of Lachish (1973-1985), Vols 1-V, , Tel Aviv University/Institute of Archaeology.

Ussishkin, David. Biblical Lachish. Israel Exploration Society/Biblical Archaeology Society

Plus numerous newspaper articles of the day.

[2]It was this same King Nebuchadnezzar who built one of the seven wonders of the world, the hanging gardens of Babylon, so that his mountain bred wife would feel at home in the city.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed