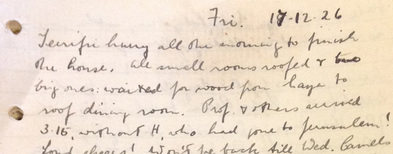

| By Amara Thornton “Opening Chorus If you see Fun in archaeology You must come and be A member of our band … Maybe you’re keen To say you’ve seen Sheykhs in their desert tents If you draw and write Like lunches light Study all night – you’ll do!” It’s not the best poem I’ve ever read, but despite its flaws this “Opening Chorus” evokes the life into which a 24-year old Gerald Lankester Harding entered when he left England in November 1926, bound for Palestine. It is one of a collection of verses found in Harding’s archive; he probably penned it during his first excavation at Tell Jemmeh, an ancient site 18 miles from Gaza. |

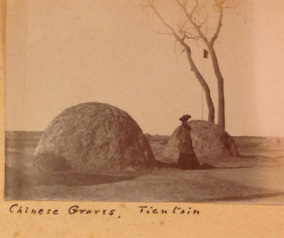

| Harding was already a well-seasoned traveller by the time he went to Palestine; born in Tientsin (now Tianjin), China in 1901 as the Boxer Uprising was ending, he grew up in Singapore before settling in England with his family in 1913. It was in London that, alongside his paid employment, Harding began studying Egyptology in Margaret Murray’s evening classes at University College London (UCL). Through Murray, Harding met Flinders Petrie, Professor of Egyptology at UCL, who ran the British School of Archaeology in Egypt (BSAE) – a training scheme for prospective archaeologists. Petrie had made his name excavating in Egypt, but for the 1926/1927 excavation season he and his wife Hilda were moving their entire operation to Palestine in search of more favourable conditions for excavators. The Petries continued to work in Palestine for the next decade. |

Tell el-Ajjul was the next site to undergo excavation. A mere six miles south of Gaza, Petrie and his team, including Harding, the Starkeys and Olga Tufnell, set out to uncover the occupation history of the site. After two seasons Starkey, Harding and Tufnell left the Petries to begin their own excavations at Tell ed-Duweir, a site between Gaza and Jerusalem, with funding from industrialists Henry Wellcome (pharmaceuticals) and Charles Marston (Sunbeam bicycles). These excavations eventually resulted in the important discovery of the Lachish letters, pieces of pottery with ancient Hebrew script in ink identifying the site to be the location of the Biblical city of Lachish.

The Wellcome-Marston Archaeological Expedition to the Near East (the formal name of the Starkey-Harding-Tufnell excavations) remained at Duweir from 1932 to 1938. Harding left in 1936 to take up the post of Chief Curator of Antiquities in Transjordan, across the Dead Sea, but he remained actively engaged in the interpretation and publication of the Lachish letters in the years that followed. Eventually he became Director of the Transjordan Department of Antiquities, but it was as its Chief Curator that he embarked on one of the most publicised excavations of his career. In February 1949 he set out with a team of archaeologists to excavate a cave at Ain Feshkha east of the Dead Sea, an area then under Jordanian control, where two years previously Bedouin had discovered the earliest known Biblical texts handwritten on delicate leather: the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Harding and his team discovered more scroll fragments at Ain Feshkha, establishing the authenticity of the fragments discovered there. In the years that followed he and a team continued excavations in the area, centring their investigations in the nearby settlement site of Khirbet Qumran. Over the course of his archaeological career in Jordan Harding undertook excavation and survey work all over the country, including Jerash, where he was based in the early part of his career in Jordan (and later buried), as well as Petra. His extensive work in Jordan brought the country's antiquities and sites to a wider scholarly and general audience; through conducting numerous surveys he became a leading expert in Ancient North Arabian inscriptions. Harding died in England in 1979.

I have concentrated mainly here on Harding’s early career in archaeology, as it is this period of his life that the footage we will be digitising through Filming Antiquity is most likely to cover. But it’s important to emphasise that Harding’s thirty years in Palestine and (Trans)Jordan (1926-1956) came at a pivotal period in the history of the region and the world – one that saw a world war, the gradual disintegration of Britain’s imperial system, the creation of Israel, the evolution of Transjordan into the Kingdom of Jordan, and the establishment of a border between Israel and Jordan that continues to have ramifications on both countries today. His archive holds much more information about the context of his work and life in Palestine and (Trans)Jordan, so stay tuned!

References/Further Reading

BSAE [British School of Archaeology in Egypt]. 1927. Catalogue of Palestinian Antiquities from Gerar, 1927. London: BSAE.

Drower, M. 1985. Flinders Petrie: A Life in Archaeology. London: Victor Gollancz, Ltd.

Harding, G. L. 1949. The Dead Sea Scrolls: excavations which establish the authenticity and pre-Christian date of the oldest Bible manuscripts. Illustrated London News Historical Archive [Online]. 19 October, p 493.

Harding, G. L. 1949. The Dead Sea Scrolls. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 81 (2): 112-114.

Macdonald, M. C. A. 1979. In Memoriam Gerald Lankester Harding. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 23: 198-200.

Sparks, R. PUBLICISING PETRIE: Financing Fieldwork in British Mandate Palestine (1926-1938). Present Pasts 5 (1): 2. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/pp.56.

Thornton, A. 2014. Margaret Murray’s Meat Curry. Present Pasts 6 (1): 3 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/pp.59.

Torczyner, H., Harding, G. L., Lewis, A. and Starkey, J. L. 1938. Lachich I (Tell Ed Duweir). The Lachish Letters. London: Oxford University Press.

Tufnell, O. 1980. Obituary: Gerald Lankester Harding. Levant 12 (1): iii.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed