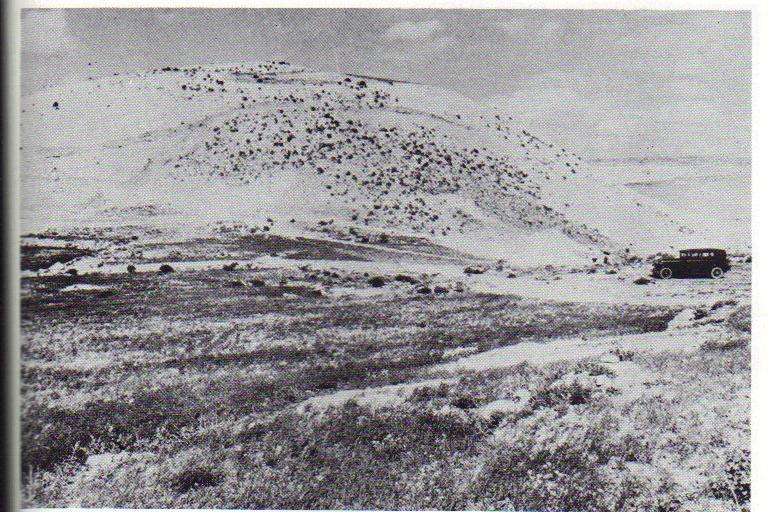

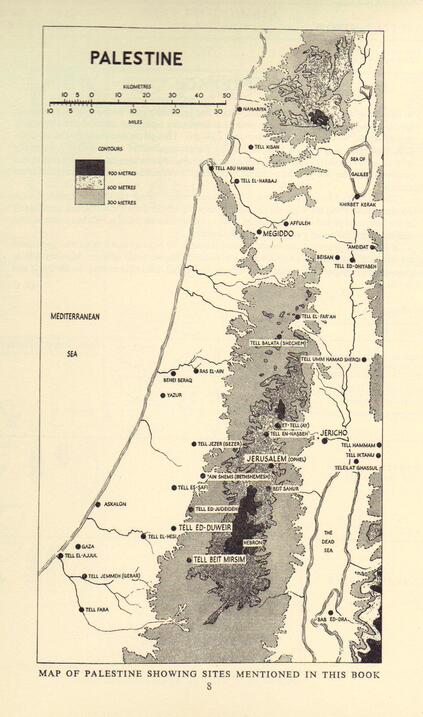

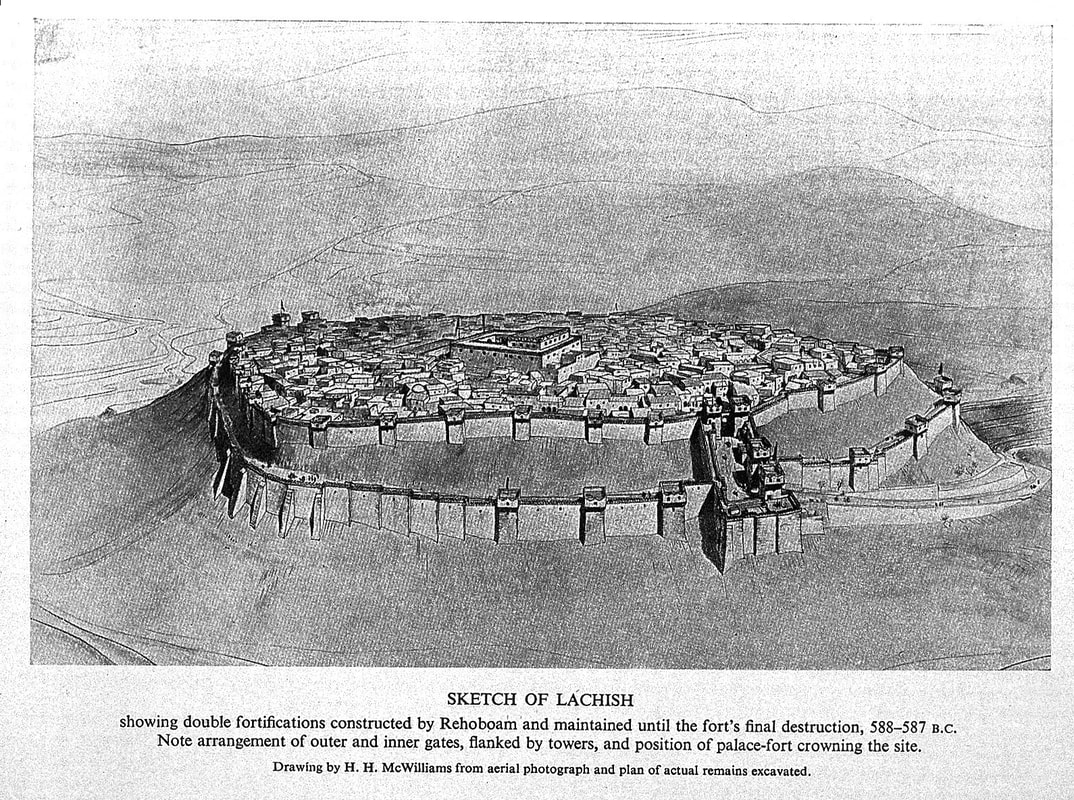

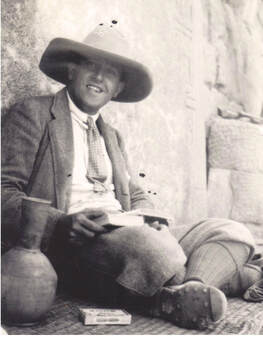

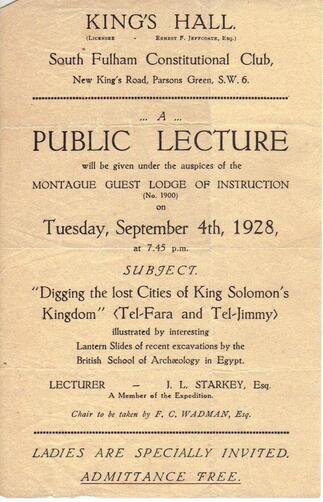

| James Leslie Starkey at Lachish, Part 2 (ii) |

| ||

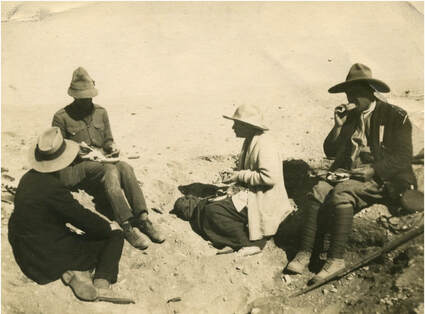

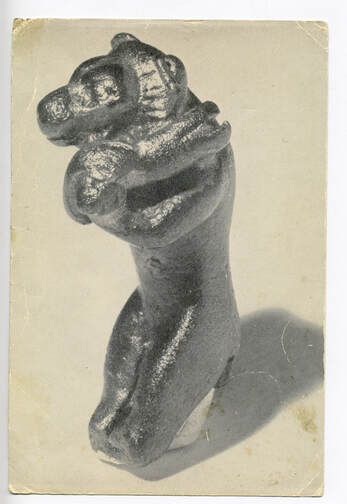

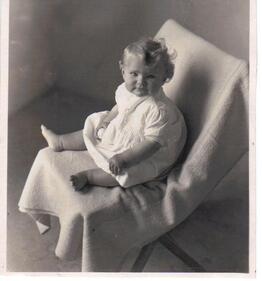

| James Leslie Starkey at Lachish, Part 2 (iii) |

| ||

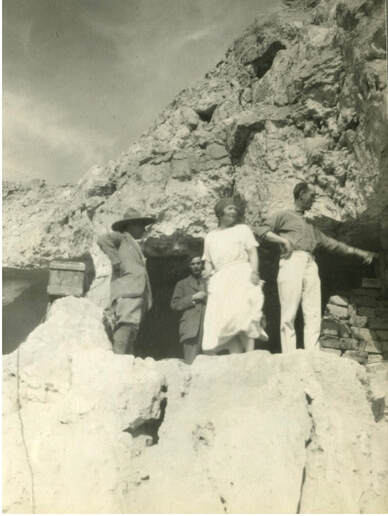

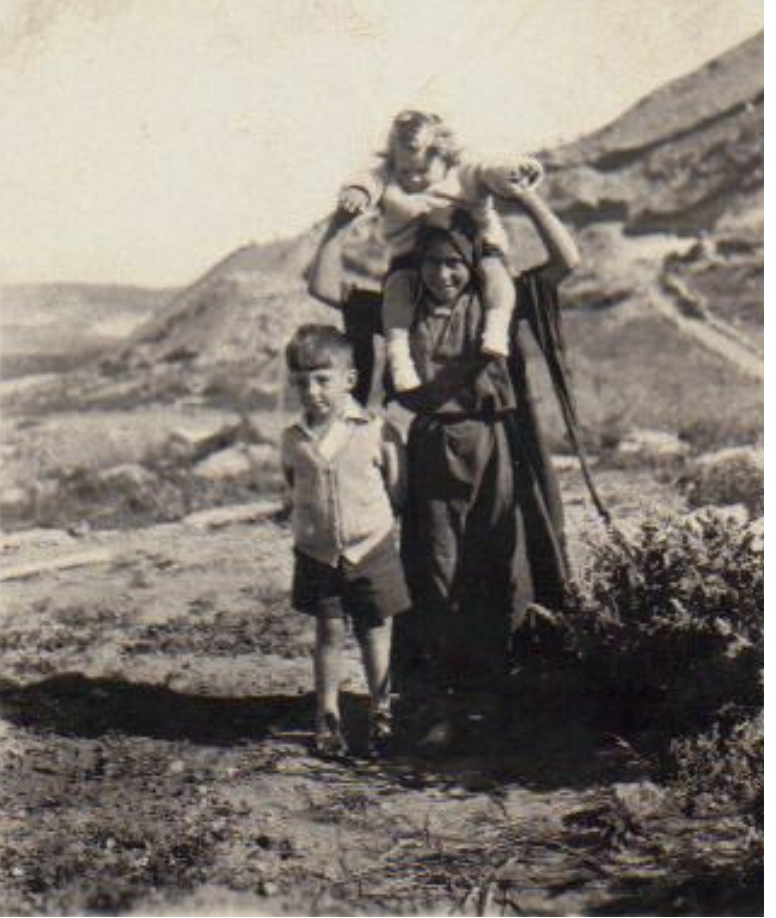

| James Leslie Starkey at Lachish, Part 2 (iv) |

| ||

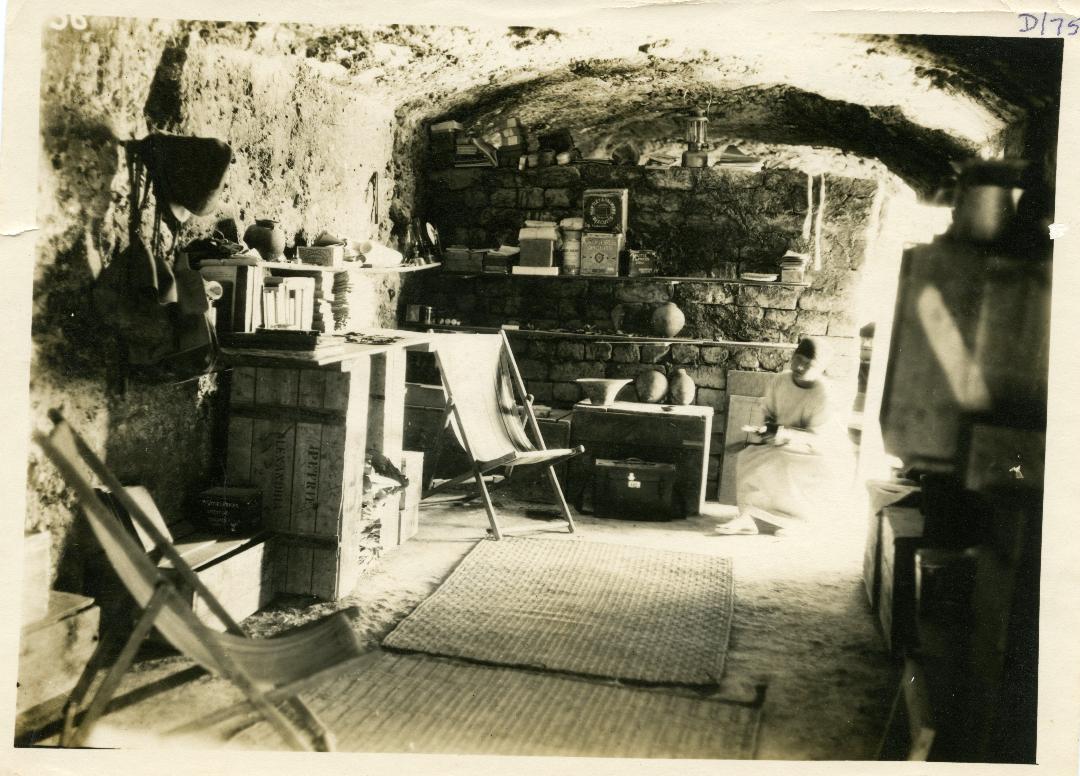

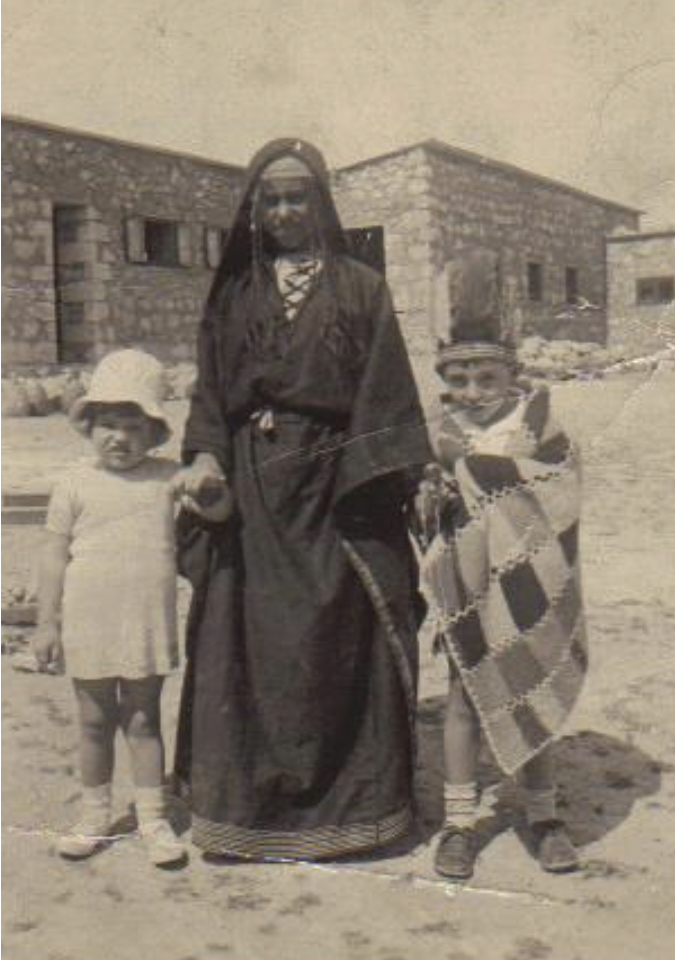

| James Leslie Starkey at Lachish, Part 2 (v) |

| ||

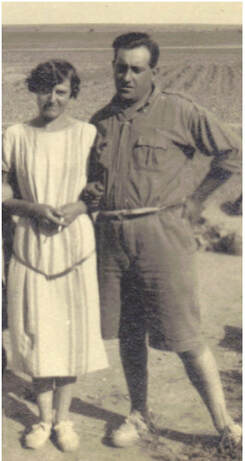

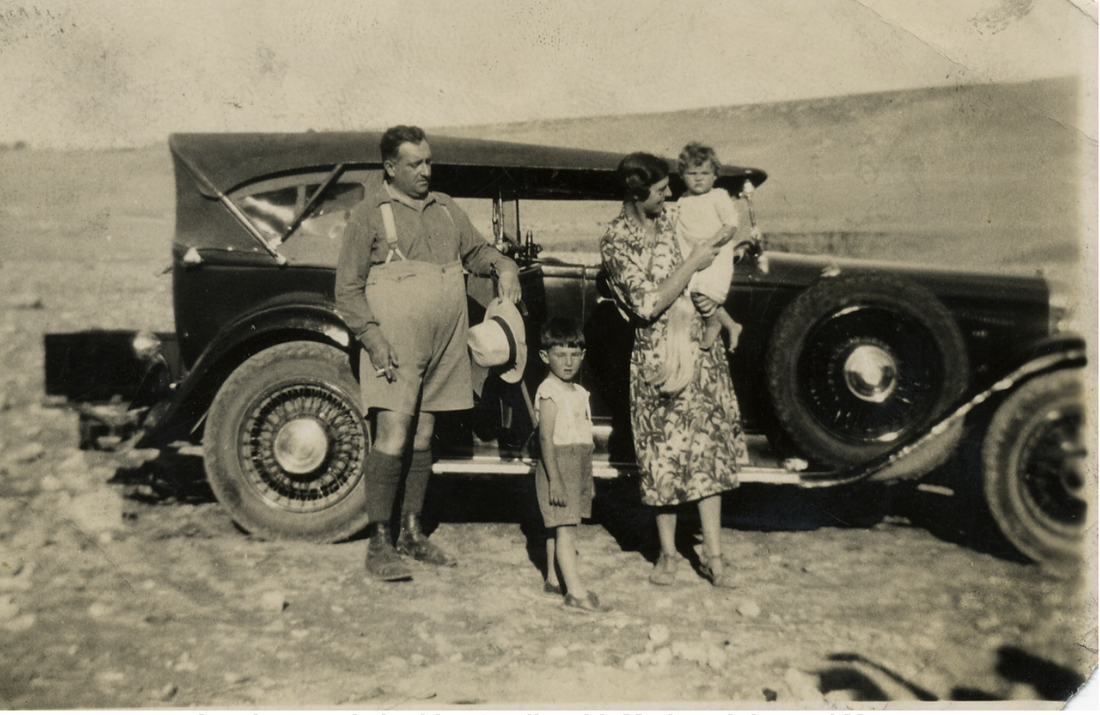

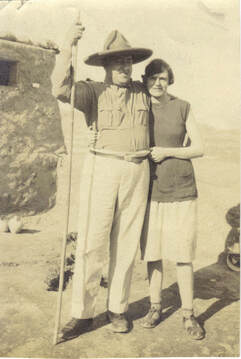

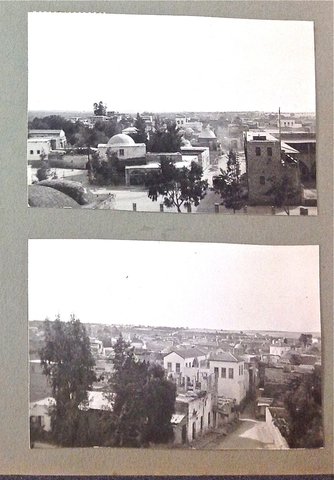

| James Leslie Starkey at Bethlehem |

| ||

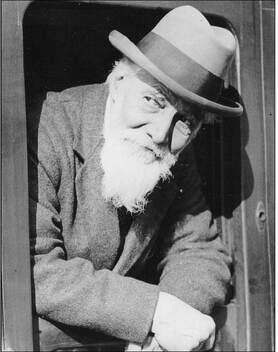

| James Leslie Starkey Tragedy in Palestine 4 i (a) |

| ||

| James Leslie Starkey Tragedy in Palestine 4 i (b) |

| ||

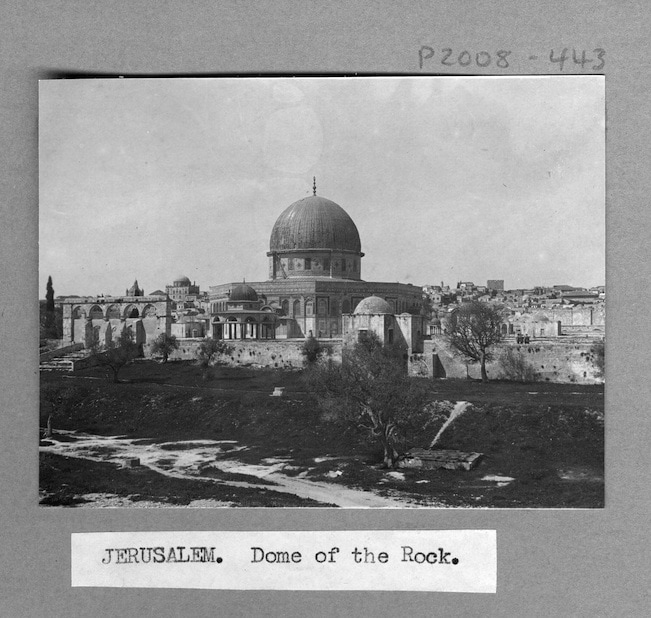

| James Leslie Starkey Funeral Jerusalem Part 4 (ii) |

| ||

| James Leslie Starkey Memorial Service London Part 4 (iii) |

| ||

| James Leslie Starkey Lachish Carries On Part 5 |

| ||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed