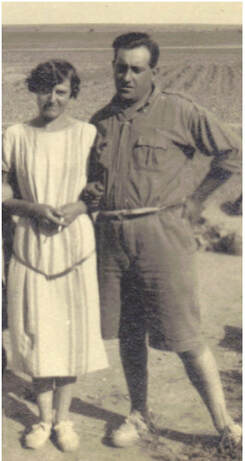

By Wendy Slaninka (Granddaughter of James Leslie Starkey & Marjorie Starkey by their daughter Mary)

This is my fourth article for the Filming Antiquity Blog regarding Harding’s archaeology footage and links in with my first, second and third articles, ’Olive Starkey – Lady of Lachish’ (Leslie’s sister), ‘Living at Lachish – Life in Camp’, and ‘First Lady of Lachish – Marjorie Starkey and her family’, where there is other information and photos of Leslie. All the Photos in this article are from the family collection unless otherwise stated.

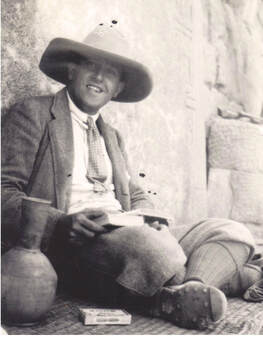

It has struck me in writing my three previous articles that I really ought to put something on the blog about the main man himself - James Leslie Starkey! There is already some family background on him and photographs in Olive Starkey’s article, and other general bits and pieces in the others but I thought it would be nice to write a short piece about his career leading up to Lachish, and about him. His life and career is well documented and known but just the same I may have something of interest or new to say!

I am sorry I never knew my Grandfather but I think his son John, my Uncle, takes after him in many ways and I take a sense of his persona from him. Olive, Starkey’s sister, introduced John to her friend Margaret Howard and she also must have sensed this too as she later wrote to Olive ‘having met his son I can now well realise the charm that Leslie must have had and his great grasp of so many subjects’. His children’s few memories of him are of a loving family man, willing to get down on the floor and play with them, carrying them round on his shoulders, and John particularly remembers him taking them to London Zoo and the cinema.

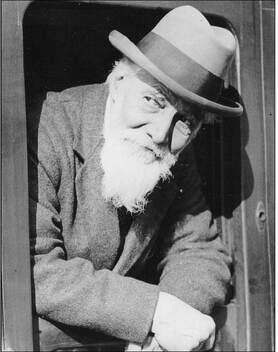

As a rather delicate child Leslie missed out on a lot of formal education (similar to Sir Flinders Petrie whom he later worked for), but his interest and passion for antiquity was fostered by books, particularly by Layard’s Nineveh, a Victorian sensation, which he had asked for as a birthday present. When he was 15 he worked for an Antique Dealer in London where he handled fine things and speculated about their origins. The premises were very close to the British Museum and he spent his spare time reading and visiting London galleries, including the British Museum and its Reading Room.

A postcard home to his sister Olive from Portsmouth mentions his passing through Southampton with 60 transporters and ships in the harbour filled with troops and horses, the common itself a mass of tents with soldiers waiting to embark. In another from Southsea he wrote that the searchlights at night were wonderful to behold. At one time he was posted to a lighthouse for some months on coastal reconnaissance, and in those lonely hours he laid the foundations of his archaeological knowledge by reading text books which he had sent out to him.

After the war – between 1919 and 1922 - he attended evening classes in Egyptology at University College, London where he came in contact with Flinders Petrie and Margaret Murray, studying hieroglyphs with the latter. Throughout this time he also attended UCL lectures when he could for the degree course in Egyptian History. Dr Samuel Yievin, whom Starkey later worked with, was on the same course and mentions his attendance in his obituary on him.

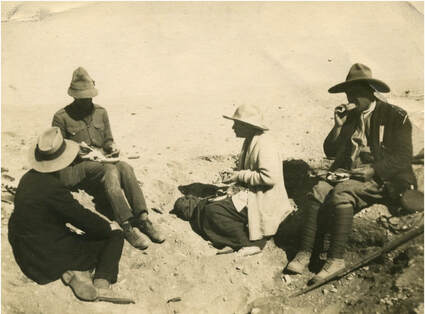

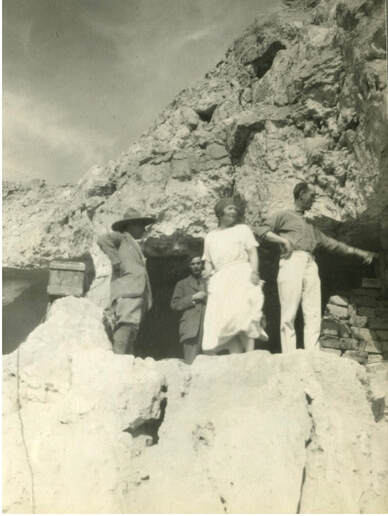

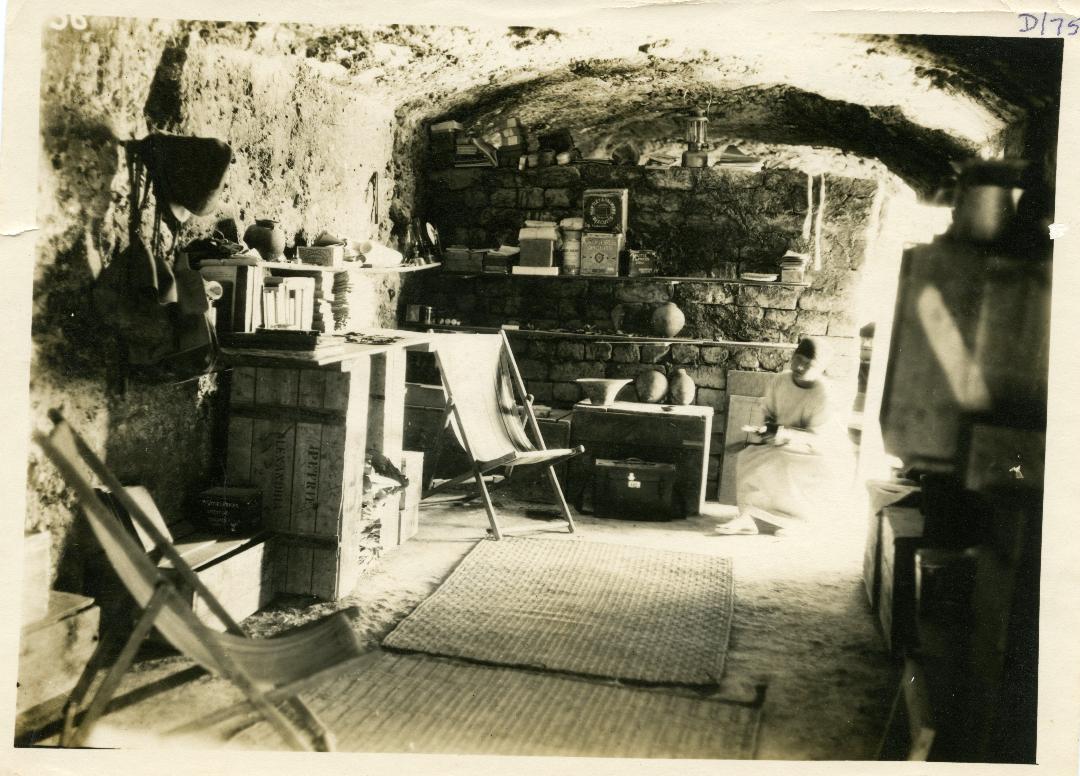

His first assignment was at Qau with Guy Brunton (Petrie’s Chief Assistant), for the British School of Archaeology in Egypt (BSAE). Qau (Qau el Kebir) is situated on the east bank of the Nile, in Middle Egypt – north of Karnak and Luxor. Obviously excited by his first trip to Egypt he sent Madge (his fiancée) a flurry of daily postcards describing their journey to the site, the site itself, their cave bedrooms, what they did each day, what they ate etc. – they make fascinating reading. The food seemed to be variations on the following theme: bread, boiled rice, hard-boiled eggs, oranges, grapes, nuts, milk, chutney, jam tart and invariably tinned pilchards or tongue! (tinned fish seemed to be Petrie’s stock in trade fare) – and ‘not forgetting coffee’.

Later back home Starkey proudly named their new home ‘Badari’. And it was also here, in March 1923, that he also brought to light one of the very earliest copies of the Gospel according to St. John by insisting on emptying the sand from about 2,000 pots which were blank apart from this priceless 4th century Coptic papyrus manuscript, dated at approximately 400 AD, and a hoard of gold coins in another! They had lain undiscovered for 13 centuries. The manuscripts are described in detail in The Expositor, April 1924, and are now stored in the University of Cambridge Library.

He also helped with the distribution of Petrie’s excavations from Abydos – The Tombs of the Courtiers, back in the UK and in particular he visited Bexhill Museum and liaised with the Curator to fill gaps in their collection. He himself even donated 1 guinea to this end!

His notebooks of progress in the field, and records of finds and observations illuminating the daily lives of these ancient people, the mound surveyed and subdivided into areas and sub areas, and the drawings and plans within this framework, were to prove invaluable to those who continued the excavations after him as the structures throughout the site could be traced in detail.*

He also regularly sent back textiles to the Bolton Museum of Textiles, and textile fragments which apparently are catalogued under ‘S’ for Starkey! Guy Brunton had also sent Bolton Museum textiles from Qau and Badari too. Although he was by then Director of Karanis, Starkey also returned to Qau in Spring 1925 to help the Bruntons close the season as Guy Brunton was ill and had been taken to hospital.

Between May and June 1926 Starkey re-registered with UCL and attended Petrie’s lectures in Egyptology, for the princely sum of £1 1/-. However, when the BSAE transferred their work to Palestine in 1926, Starkey rejoined Petrie as his first assistant at Wadi Ghazzeh and Tell Jemmeh, near Gaza – an ancient fortress along the course of the Wadi Ghazzeh. Together with Harding, he was the backbone of the Petrie expeditions at Tell Jemmeh (1926-27), Tell el Fara (1928-29) and Tell el Ajjul (1930 onwards) – all in roughly the same area - excavating three of the great fortified mounds of the ancient Syro-Egyptian frontier, and leading the first and final season at Tell el Fara (also known as Beth Pelet) in Petrie’s absence. By now his son John had arrived (born 1929) and he accompanied his parents on the expeditions. His daughter Mary was born in October 1931 so Lachish was her first outing.

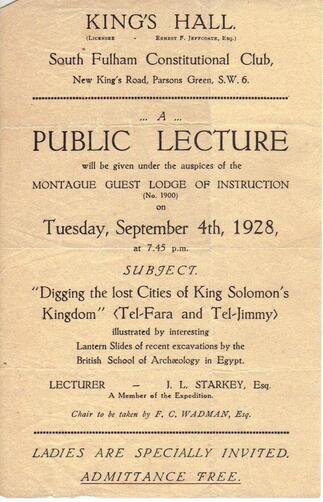

In 1927 he was elected to the Royal Anthropological Institute. This interesting poster is of a lecture he gave in 1928 to a Masonic Lodge – the title is certainly attractive and I especially like the last line ‘Ladies are specially invited’, presumably meaning the content and nature of the lecture would be suitable for ladies to attend! After the lecture the Lodge wrote enthusiastically thanking him for ‘such an intellectual treat’. Starkey’s father in law was a Masonic Lodge Master and Starkey himself became a Mason in 1929.

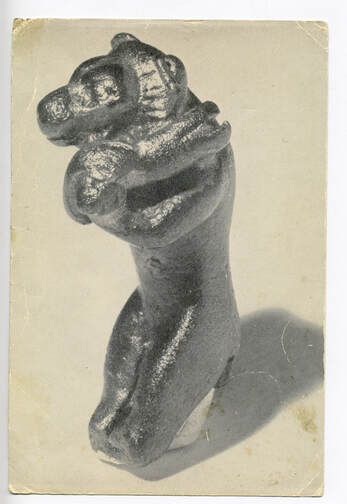

Whilst at Tell el-Fara Starkey discovered the Bronze Bear, from the reign of David or Solomon – originally loaned to the Victoria and Albert Museum from the Institute of Archaeology. Now back in their possession it is affectionately known as the ‘Starkey Bear’. I have a V&A postcard of the Bronze Bear which Olga Tufnell sent Mary saying ‘Your father found this’!

In 1932 Starkey parted company with Petrie and struck out on his own, as Director of the Wellcome-Marston research expedition to the Near East, to excavate Lachish. Sadly for Petrie, Olga Tufnell and Lankester Harding went wih him. Even Petrie’s Cook, Mohammed Kreti, who had been with the Petries since a boy, followed suit.

TO BE CONTINUED, with a further article on Lachish.

Sources/Further Reading/Research:

BSAE, 1923, The Gospel of St. John, Sir Herbert Thompson

BSAE, 1923, Qua and Badari I, Guy Brunton

BSAE, 1924, The Badarian Civilisation, Guy Brunton and Gertrude Caton Thompson

The Expositor, April 1924 No.4, R Kilgour, Hodder & Stoughton

Cambridge University Library, the Coptic Scripts

University of Michigan, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology

Bolton Museum of Textiles – textiles sent by Starkey from Karanis

Petrie Museum, University of London Institute of Archaeology

Qualley Log: Diary of Karanis 1924-1925: https://www.luther.edu/archives/assets/Qualley_Log_1924_25.pdf

BSAE, Beth Pelet I, 1930, Flinders Petrie, including contribution by James Starkey

BSAE, 1930, Corpus of dated Palestinian Pottery, J. Garrow Duncan, including Beads of Beth Pelet by James Starkey

BSAE, 1932, Beth Pelet II: Prehistoric Fara, E McDonald, including Beth Pelet Cemetery by Lankaster.Harding and James.Starkey

An Appreciation, PEQ, 1938, Olga Tufnell

Petrie in the Wadi Ghazzeh and at Gaza: Harris Colt’s Candid Camera, PEQ, 1979, Francis W. James

Reminiscences of a Petrie Pup, PEQ, 1982, Olga Tufnell

*The old black and white photos of the excavations at this time were used in the making of the Indiana Jones film The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed