In an earlier post, Amara Thornton talked about Gerald Harding’s colourful career in archaeology, from his introduction to Egyptology through Margaret Murray’s lectures (they must have been good - he kept his notes), to learning Arabic from his Bedouin co-workers in the Wadi Ghazzeh while learning the trade of archaeology.

Harding owed the start of his career to Petrie’s patronage; this post explores his ‘apprenticeship’ years - from his first dip into a Petrie dig at Tell Jemmeh in 1926, to the time he left the Petries in 1932 to join new excavations at Lachish.

Details of these have been gathered together from a range of sources, from Harding's own diaries and photographs, to letters written by fellow digger Olga Tufnell, and the diaries, letters and biographies of Flinders Petrie and his wife Hilda.

Gerald Harding began his Middle Eastern adventures in style, traveling out to Egypt with Petrie and Hilda on the S.S. Champollion in November 1926. Petrie described it as a ‘perfectly smooth passage’ [1], so I’m guessing the life jackets seen swaddling Petrie and company in the image above were not required.

The party disembarked in Egypt, allowing Gerald to add some pyramid images to his photo album, before an uncomfortable night journey to Gaza. This is where Harding’s life in archaeology really begins.

Chapter Two: In which Gerald develops a taste for dirt archaeology

The first site that Harding worked on was Tell Jemmeh: a small, somewhat unimposing mound in which several centuries of occupation failed to impress. In a rather desultory way his diary reports finding walls, nearly complete pots, querns, beads and the occasional scarab, alongside less welcome trench companions such as scorpions (18 in one day), a snake (‘fairly large’), and a tarantula (‘horrid beast’) [2]. Although the site was later to prove fruitful for a team from the Smithsonian Institution, Petrie clearly felt that it had been exhausted after a few month's work, and the next season moved his diggers on to excavate another site in the region - Tell Fara.

Tell Fara proved more exciting for everyone, with a range of prehistoric sites to explore nearby, as well as a long sequence of occupation from the Middle Bronze through to the Roman period on the main tell. The dig team spent four seasons here from 1927 to 1930. During this time, the Petries were often absent, and a tight field unit developed with Leslie Starkey, Gerald Harding and Olga Tufnell at its core (or ‘the old firm’, as Tufnell put it). Gerald was put in charge of a gang of men, whom he led out onto the main tell or took out to explore the various cemetery fields that produced some of the site’s more spectacular finds. He and Olga began a competition to see who could find the most scarabs; history has not recorded who came out the victor, although the scarab count was certainly high.

The final Petrie site that Harding worked on was Tell el-‘Ajjul, which now lies on the outskirts of modern Gaza. In antiquity, this was a small but thriving port town, with a cosmopolitan population showing strong Egyptian links. It was an inspired choice, with fabulously preserved mudbrick buildings capturing the feel of a busy Canaanite metropolis, while extensive cemeteries spread out around the base of the tell produced an array of exciting finds that are still fuelling archaeological debate today. Petrie stayed there for five seasons - but Harding was to leave after the second of these, when he and Olga were enticed away to join Starkey’s new field project at the ancient city of Lachish. This marked the end of Harding’s period of close association with Petrie, although not the end of their friendship.

Harding’s success in archaeology owed a lot to his pragmatism and all-round usefulness on a dig. He was clearly a handy man to have around, with exploits including building a car-worthy road at Tell Jemmeh, re-attaching Hilda Petrie’s roof during a disastrously windy night [3], and securing his own window against a bothersome sandstorm with a nifty arrangement of drawing board fixed down with penknives.

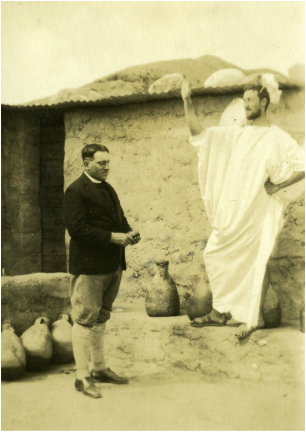

Nor was his ingenuity confined to weather proofing skills. According to Olga [4], Harding also managed to create some kind of magic lantern out of a biscuit box for showing still images at the dig, and arranged to bring a piano onto site for after-dinner amusement, which by all accounts was a great success. He was also not adverse to some amateur dramatics, taking part in some mini-ballets with Olga Tufnell and Kitty Strickland at ‘Ajjul, including one titled ‘the Palestine Waggle’ after one of Petrie’s decorative motifs. He then went on to compose an operetta called ‘the Golden Calf’ with Olga; its reception is unrecorded, although Olga’s lyrics survive, neatly typed out, in the Harding archive. These interests carried on through his life, as his later involvements with the Amman Dramatic Society, the ‘Ammaniacs’ (‘No. 1 Revue Company’) or Phoenix Players of the American University of Beirut show. It is thanks to Harding's interest in film and photography that these fleeting moments have been captured and preserved, reminding us that while archaeology may be a serious business, some archaeologists know when its time to kick off their shoes and start the party.

Sources

1. Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, Flinders Petrie Pocket Diary entry, Nov 18-20th 1926.

2. Gerald Harding Tell Jemmeh diary, UCL Institute of Archaeology Collections.

3. Palestine Exploration Fund, Olga Tufnell Archive, letter dated 25th January 1931.

4. Palestine Exploration Fund, Olga Tufnell Archive, letters dated 30th November 1930, 3rd January 1932 and 23rd March 1932.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed