Filming Antiquity is a project about amateur films of excavations. So what, exactly, are ‘amateur films’ and why study them?

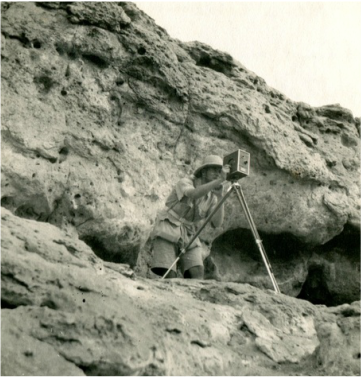

Amateur films are films made by someone working outside of a major studio or film unit, usually self-taught, and often not paid for the films they produce. They include what are commonly called ‘home movies’—those films made by a member of a family or close group of friends to record an event and replay it exclusively for this private audience—but they also include films intended for a wider audience, unknown to the filmmaker. These might be films of community life, national celebrations, historic events, or ‘causes’ that the filmmaker wants to raise awareness about. They might also be films to raise funds to support such a cause or to help the work of a small organisation. Amateur filmmaking is perhaps best described as the work of an enthusiast; this is someone who, without pay, wants to make films and chooses to film a particular event. It is this intertwining of two enthusiasms that makes amateur films crucial documents for the study of both media history and social history. They are records of an act of filmmaking at a particular moment in time and of an event deemed for some reason worthy of filming. By digitising films from the Harding archive Filming Antiquity seeks to find out more about Lankester Harding himself and about the places and people he filmed in 1930s.

This period saw an explosion in amateur filmmaking in both the UK and the US. As Patricia Zimmerman explains in Reel Families: A Social History of Amateur Film (1995), the spike in amateur filmmaking came as a result of changes in technology that made cameras and projection systems more affordable. By the late 1920s Eastman Kodak and Bell and Howell were selling these systems to mostly middle-class customers who could develop their knowledge of filmmaking through the amateur cinema magazines such as Amateur Cine World andThe Amateur Film Maker that also appeared at this time. Britain's regional media archives hold in their collections hundreds of films from the 1920s and 30s about local events and trips around Britain and abroad. Filming Antiquity will contribute to this material with its films of British Mandate Palestine.

These films, then, can be studied by those interested in archaeology, interwar social history, the history of the Middle East, and the history of cinema. In particular, they can help us to think about amateur film as social practice and cultural artefact, a subject Filming Antiquity recently explored at its launch event with footage from the work of the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) at Tell el-Amarna as case study.

| The EES films were made between 1931 and 1933 by Hilary Waddington and Stephen Sherman. At the launch, I discussed what they can tell us about several complex and overlapping interactions: between archaeologists and artefacts, British subjects and local cultures, modernity and antiquity. More broadly, I argued for the inclusion of excavation footage in ongoing studies of amateur film, an expanding field that until now has not included this rich material. The EES footage features as its star the director of the dig John Pendlebury. Pendlebury guides workers in the movement of objects and directs them in leisure activities during a Christmas fantasia. He encourages some group bonding among the British members of the dig team in a private moment of friendly competition as the camera captures a high-jump contest. |

| And he hams it up dressed as a disgruntled local worker. These social sequences make the films a fruitful resource for studies beyond archaeology and Egyptology, though the footage contains several scenes of the particulars of the dig and rare shots of the process of 'division' (where finds were divided between excavators and government authorities) at the Cairo Museum. Follow the Filming Antiquity project to find out what the Harding films will share and what they can tell us about interwar excavations and the wider interests of Gerald Harding, amateur filmmaker. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed