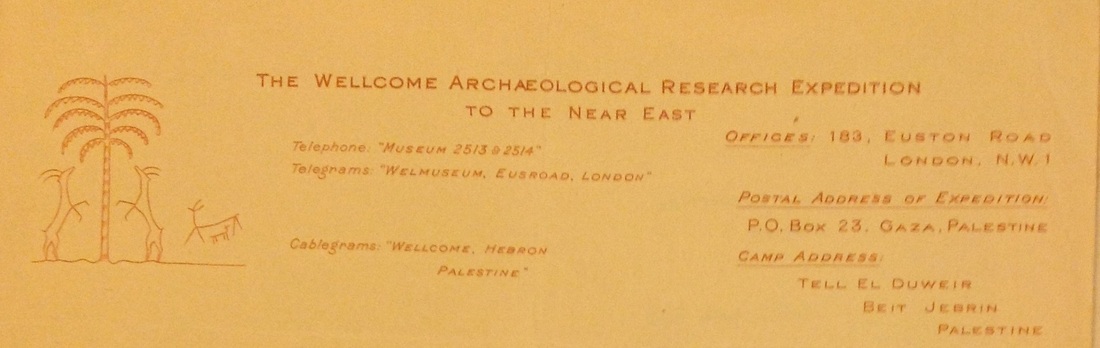

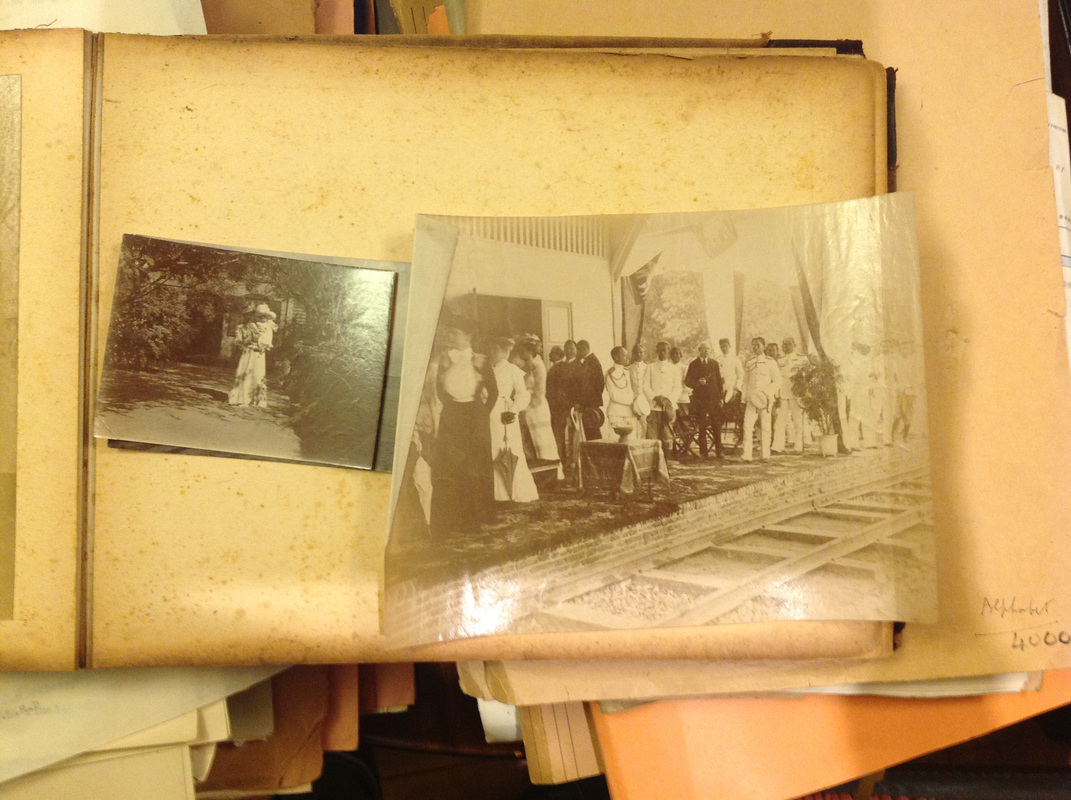

| Gerald Lankester Harding made an important record of life and excavation techniques on Near Eastern archaeological sites in the early 1930s. His record was especially unique in that he used movie film, enabling us to see the life people led and the working techniques they employed in motion rather than in still photographs. Apart from the interesting archaeological work we see, we also get an idea of the workers’ hard physical labour, the way they lived and something of their characters. We also see the archaeologists in charge, their characters and some of the fun they had. They become human for us rather than us just knowing them from their serious academic work. Lankester Harding was able to record all this because he had access to 9.5mm cine cameras. 9.5mm was the first amateur cine gauge but it was invented and started life for a very different reason. |

In 1912, Thomas Edison had come up with a 22mm wide film with three sets of pictures, used in his ‘Home Kinetoscope’. This system proved impractical and was restricted to what the Edison Company decided to release. The Edison system proved not to be popular enough and was dropped. Meanwhile, the French (Pathé Freres) launched, in the same year the ‘KOK’, or ‘COQ’ projector that used a 28mm film gauge. This format proved very successful and became widely distributed. Pathéscope Ltd opened an office in London at 64 Regent Street for the distribution of the films. Many of the 28mm releases were documentaries with titles such as: Ice Breaking in Finland and Prayer Time at the Great Mosque, Delhi. There were also moralizing films, including the title In the Grip of Alcohol. Lighter, comedy films of European performers such as Charles Prince and “Little Moritz” proved popular.

In 1914 Pathé tried to make inroads into the US film market and there was some success but the war intervened and things slowed down. Then an American inventor, Willard Beach Cook, came out with his own design of equipment in competition with the Pathé machine. After the war, Cook expanded his business in the US with films of more popular appeal. There were Hollywood releases such as Chaplin farces, Douglas Fairbanks action films and westerns, starring William S. Hart. The Pathéscope offerings were, by comparison, rather less exciting - Mr Smith’s Small Feet andThe Pork Butchers Nightmare among them.

| Pathé decided it needed a new approach and set a team to work under engineer Louis Didée. The plan was to come up with a completely new format. Didée and his team hit on the idea of using existing 35mm film and splitting it into three. The way it was done was to load the unexposed film, in darkness, into a machine that used the 35mm sprocket holes to drive the film. As it progressed through the process, it was cut into three strips of 9.5mm film. New sprocket holes were punched in the middle of each of the new strips, producing three rolls of 9.5mm film. At the end of the production line, the 35mm sprocket holes, no longer needed, were cut off. |

| Thus was born 9.5mm, that was to become the first real amateur film gauge. The film was launched by Christmas 1922. Nine metres (30ft) of the new film was loaded in cassettes. The Pathé trademark was a chick emerging from a shell and the slogan was "Le Cinema Chez-soi" ("Home Cinema"). The films could be shown on the ‘Pathe Baby’ projector, equipped to take the cassettes. The new format took off in popularity and film cassette sizes increased to 15m (50ft) and 30m (100ft), the larger cassettes became known as "G" for "Grand". Over 300,000 projectors were sold in France and the UK. The Pathéscope office in London became 5 Lisle Street, off Leicester Square. |

To be continued...

References/Further Reading

Moules, P. (ed). A Brief history of 9.5 [Online].

Newnham, G. Pathefilm.uk [Online].

RSS Feed

RSS Feed