At the end of April, Filming Antiquity screened two different excavation films at the Petrie Museum for the “Capturing Light” event. These two films, of Henry Wellcome’s excavations at Jebel Moya, Sudan (1912/13) and Egypt Exploration Society (EES) excavations at Amarna, Egypt (1930-1933), were made at very different periods. The Wellcome film is more or less “Edwardian” and the EES film very much of the inter-war era. Between the two periods there had been many advances in film and filmmaking including the invention of clockwork camera motors yet we still see Hillary Waddington using a hand-cranked camera in his 1930s Amarna film.

I received a Diploma in professional film production at the London Film School, and then worked at the London Film School in the editing department before coming to study Archaeology at UCL. While research into the archives relating to these films is ongoing, I will offer some insights into the kinds of equipment and techniques used during these eras to capture these fascinating moving images.

The Cameras

Frank Addison makes no mention of the filming in his 1949 site report on Jebel Moya, but recent research by Angela Saward, the Wellcome Library's Curator of Moving Image and Sound, suggests the cameraman was expedition photographer Arthur Barrett (more on him in a future post!)

At present it is unclear what kind of movie camera was used to film the 1912/13 Jebel Moya season, but at this early stage in filmmaking, it was the French and British that led the field. There are a number of candidates for the camera used, including British made movie cameras such as the Williamson or the Moy and Bastie. Although it was not imported to Britain until 1914 the French made ‘Debrie Parvo’ (‘Parvo’ meaning ‘compact’) invented in 1908, was widely used by the time of the Jebel Moya excavations. Wellcome, a wealthy man and someone who might want the best and could afford it, could still have privately imported the advanced Debrie.

There was no 16mm film in the early 1900s and the Jebel Moya film was shot on 35mm film. The Debrie Parvo would have held 390ft of film which was hand-cranked and would have lasted 6 minutes at 16 frames per second. It was encased in a wooden box but it had an inner metal case and workings of metal. This would be an advantage in places like Africa where mould and insects had been known to attack wood and leather.

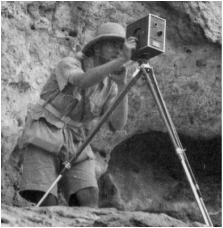

| In this image in the EES archive from Amarna in the early 1930s we see Hilary Waddington using a hand-crank cine camera which was in fact a ‘Cine-Kodak Model A’. Originally known as just the Cine-Kodak, it was invented in 1923 to work with the new 16mm film. Within just two years Kodak had developed a Cine-Kodak with a clockwork motor. They called this the Cine-Kodak Model B, and so it was from 1925 that the first hand-cranked Cine-Kodak became known as the Model A. This means that there were alternative, clockwork cameras like the Model B that Waddington could have used at Amarna. It makes one wonder why he chose to use what was by then an old fashioned camera; maybe it was cheaper to purchase? |

Being hand-crank cameras, both the Jebel Moya and the EES Amarna cameras would have had to be tripod mounted. The Cine-Kodak Model A was also 16 frames per-second - it was really an amateur camera compared with the earlier Debrie Parvo, which was considered ‘professional’.

The Debrie allowed the camera operator to focus through the 'taking lens' - the lens the film was exposed with. This was achieved by having a 'ruby window' (red filter) in the viewfinder. Because the film was more or less 'orthochromatic' (only sensitive to the blue and green light of the spectrum) the red filter enabled the operator to view through the taking lens without affecting the exposure of the film. As I understand it, the film could be moved to the side and the image viewed directly, or on a ground glass; the image was upright. Once focused the 'ruby window' viewfinder could be closed and the operator would then use the side-finder for normal filming. Another plus for the Debrie was the ability to alter the shutter speed.

All this was quite a contrast to the later amateur Cine Kodak Model A Waddington used at Amarna. This camera had a 'fixed focus' standard lens (25mm, being a 16mm camera) with the camera operator having to use the built-in finder that did not see through the taking lens and gave an upside down image. It was not in fact until the 1940s that the German company ‘Arriflex’ invented the rotating mirror shutter mechanism that camera operators could see a high quality image through the lens whilst filming. There were sophisticated side finders and prism finders before this like the ‘Mitchell’ but the Arriflex device was the great breakthrough.

Exposure might have been difficult for the Debrie with no exposure meters at the time, but the operator could have relied on charts suggesting the right f-stop - the lens aperture opening - for various lighting conditions. Exposure meters were just coming in when Waddington began filming in the 1930s. The f-stop and film stock light absorbing speed, its American Standards Association rating, were the only variables as far as exposure was concerned because the shutter speed was fixed on the Cine Kodak Model A. Stock would have been cheaper for Waddington to buy because whereas 35mm comes out as 16 frames per foot the new 16mm was 40 frames per foot.

With hand-cranking, any variation in the cranking speed could have resulted in a change of exposure. Slightly slower cranking would lead to more light on the film and overexposure. This may account for fluctuations in the filmed image when the film sometimes becomes lighter or darker. This fluctuation does not happen with motorised cameras that keep to speed.

Waddington achieves slow motion in part of the EES Amarna film. To accomplish this effect Waddington would have had to increase his hand cranking and at the same time open his aperture to compensate for less light reaching the film. Alternatively, he could have printed each or every other frame twice which would have had the same effect for the audience. We would need to see the film-frames to know for certain how it was done, or look at the digitised version frame by frame.

Another feature of all films, hand-cranked or motorised, is the ‘flash-frame’. This is a portion of overexposed film just at the start and finish of a ‘take’ and is due to the camera running slow at these times. A classic sign of un-edited ‘rushes’ (the first ungraded or ‘one-light print’ of a film for viewing by the director and editor) is the inclusion of flash-frames. Flash-frames would normally be removed by the editor in a finished film. Interestingly, in the sequence showing the “division” of artefacts in the 1930s Amarna footage what look like flash-frames appear. The footage also includes film information boards describing the shots. Normally these boards are only used by the editor and would be removed from the finished film. All this suggests at least some of the Amarna footage that was digitised was unedited.

Survival

We know John Pendlebury gave some film shows of the EES Amarna work (e.g. at the Society of Antiquaries) so there may be a finished film still surviving somewhere. The EES Amarna films that were scanned onto VHS (and then unfortunately disposed of in the 1980s) look like they might have been just the unedited ‘rushes’ and not the finished film.

The Jebel Moya film was ‘Nitrate stock’ and prone to dangerous deterioration, while Waddington’s film was Cellulose Diacetate safety stock invented in 1923 and used to make the early 16mm films. Movie film nitrate stock was only ever produced in 35mm and done away with in 1951. The Jebel Moya film stock eventually deteriorated and was destroyed, but the Waddington film stock survived. Both films would have had negatives - the Jebel Moya negative is lost to us, but could the Amarna negative have survived?

Futher Reading

Raimondo-Souto, M. 2006. Motion Picture Photography: A History. Mc Farland Co. Inc.

Salt, B. 2009. Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis. (3rd edn.). Starword.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed