Continued from Part 1.

Small 9.5mm ‘Pathe Baby’ movie cameras had been available since 1923. At first they were hand cranked but from 1926 the possibility of an attached clockwork motor ‘Motrix’ was introduced. Then in 1931 (tying in quite well with the Lankester Harding films) came the 'Pathe Motocamera' and then the ‘World B’ model, which both had built-in motors. We don’t know exactly what camera Lankester Harding was using for filming but we can be pretty certain that it was one of the new motorised cameras because there is a classic 'giveaway' shot: we see the view point of the camera on a tripod filming a wall and in a couple of seconds Lankester Harding walks into shot and poses on the wall for the camera. He then exits but the camera remains rolling, whilst he would have made his way back to turn it off. This is exactly the kind of thing people with a motorised camera do when the want to be in a film but are by themselves at the time.

As far as exposure was concerned, Lankester Harding might well have used the Pathe ‘Posograph’, a chart/calculator made of card that gave some guidance on the correct exposure for certain conditions. However, a relatively new invention was the ‘Extinction meter’, like the ‘Drem Justophot’. The extinction meter relied on a series of numbers or letters seen through a viewer like a small telescope. The letter or number just in view was the correct exposure. On the barrel of the device a table of settings for the camera could be used to adjust shutter speed and aperture, rather like a modern 'spot meter’.

Having been invented in 1924 the ‘Drem Cinophot’, designed specifically for movie making, linked more to a fixed shutter speed. It was improved in 1928 to make it more sensitive; just a few years before Lankester Harding was to make his films. It is very likely that Lankester Harding used an extinction meter because that was the latest most practical technology. There was a photoelectric meter in 1931 called the ‘Electrophot’ sold by J. Thomas Rhamstine, of Detroit, Michigan - but it weighed 1.5 lbs. and was not very portable like the modern light meters.

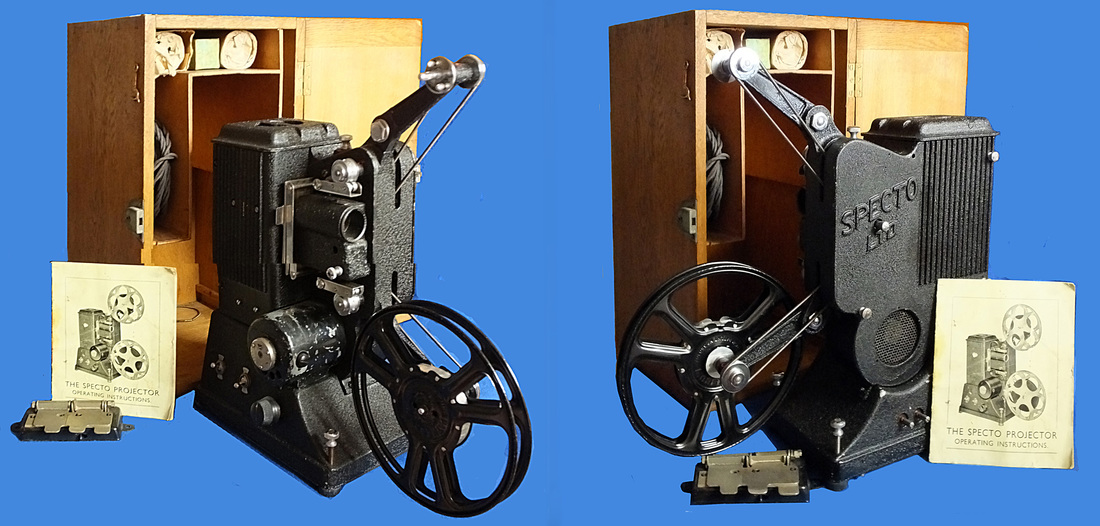

Around Europe the market for 9.5mm cameras and projectors grew with the Swiss producing the ‘Pailliard Bolex’ brand and the Austrians the ‘Eumig’. In the UK makes such as: ‘Campro’, ‘Midas’, ‘Coronet’, ‘Binoscope’, ‘Dekko’ (which might well have come from the British army bringing back the word ‘Dekho’ (‘Look’ in Hindi) from India, hence the old British phrase ‘Have a dekko’ (‘Have a look’). The best British make of projector was the ‘Specto’ made by Specto Ltd of Windsor. The Specto Company was founded by a Czech, J. Danek.

From 1936, with the introduction of Kodak’s 8mm film gauge, 9.5mm began to decline, even though the new 8mm format could only hold ¼ of the information and image quality of a 9.5mm frame, very near, in fact, to 16mm film! The ‘commercial’ end for the format came around the mid 1960s. It is now only kept alive by enthusiasts, who meet to have 9.5mm film shows. The gauge has even been manufactured again by re-perforating 16mm film for the use of 9.5mm enthusiasts.

The story of 9.5mm film is just one piece in the jigsaw that goes to make up the history of amateur filmmaking. Pathe, for example, had also got into the 17.5mm film gauge that had been around since the 1890s but that too eventually failed.

We are so fortunate that Gerald Lankester Harding was a movie film enthusiast and has left us with such a good record of life on excavations so long ago. Film and video is a great way to communicate to the public. The person in the street who is interested in archaeology but is not a professional or specialist in the subject has the power through public opinion to support the work of archaeologists both in spirit and financially. I am sure that Gerald Lankester Harding knew the importance of sharing archaeological work with the public in an accessible way such a through movie making: we would do well to follow his lead today.

For this piece on 9.5mm film I am especially grateful for the writings and research of the late Mr Paul van Someren, Mr Patrick Moules and Mr Grahame Newham.

References/Further Reading

Edwards, B. 2000. Avebury Film Discovery. Regional Historian 6.

Moules, P. (ed). A Brief history of 9.5 [Online].

Newnham, G. Pathefilm.uk [Online].

RSS Feed

RSS Feed